This year we launched the new single honours BA Literature and Film Studies. The single honours bit is important. In a joint honours with a name like this, generally students could expect to take a couple of modules in the English department and a couple in the Film Studies department each year, with the relationships between literature and film largely unexplored (beyond, perhaps, a module on adaptation). So we set out to do something rather different – to continue to recognise medium-specificities and disciplinary knowledges/practices/skills, but also to bring them together. Various practicalities (staff specialisms and availability, institutional structures, etc) shaped the form this has taken. Basically, each year, students on the degree take one literary studies module, one film studies module, and two modules organised around a particular set of ideas that study both film and literature together; and none of these are shared with other programmes.

In the first year, one of the ‘combined’ modules looks at issues of cultural value and the other one – my one – is about representations of the city in fiction and film. Each week we have a two-hour screening slot, and a three-hour session which combines lecture and seminar activities in various mixes.

I will try to find time each week to blog about what we have been up to.

The first week of a module with new students always has particular tensions between:

1) all the institutional and organisational information that at least needs to be said aloud;

2) icebreaking;

3) encouraging students to start talking to each other and with the whole group;

and 4) actually studying something together

Fortunately, we were able to keep the first intake onto the degree quite small, and the students have already had induction sessions and a class together, so 2) could at least be folded into 3) and 4). Bureaucracies, however, tend to proliferate the items for 1) and drop them in the programme leader’s lap – in this instance, mine. Fortunately, I have great colleagues and we were able to share that load out a bit across the modules. Otherwise we might never have got to 4).

And at least everyone now knows what to do in case of fires or medical emergencies…

There is a further tension between introducing the module as a whole and meaningfully studying something quite specific that week.

In preparation for class, we read China Miéville’s London’s Overthrow and watched The Long Good Friday (Mackenzie 1981).

We began with some general questions:

- How are cities defined?

- How do cities differ from towns?

- What are the relationships between the city and the country? Between the city and the conurbation or megalopolis? Between ‘the city’ and actual cities?

- Is the city merely a physical, architectural phenomenon?

- How are cities experienced and imagined?

Which inevitably lead to our first run-in with that student-frustrating formula: there is no definitive answer.

Louis Wirth in the 1930s defined cities in terms of permanence, large population, high population density and social heterogeneity. The UN seems to be moving away from thinking in terms of cities to mapping space in terms of intensive urban agglomerations and extensive metropolition regions. In the UK, unless you happen to have an Anglican diocesan cathedral, city status is awarded by the monarch – usually after some kind of competition tied to a celebration of the monarchy, such as a jubilee or royal wedding.

Probably the most useful definition in terms of the coming weeks is Richard Sennett’s self-consciously ‘simple’ attempt from 1977: ‘a city is a human settlement where strangers are likely to meet’. Which we unpicked for a while.

The Long Good Friday

Crime movies are often good for social and political commentary. The urban crime movie, particularly as it builds on hardboiled fiction, makes use of physical mobility across the city to explore social, political and economic relationships; and by moving across class and race barriers, it is able to depict crime as mirroring and/or paralleling ‘legitimate’culture. Hollywood’s ‘ethnic’ gangster movie protagonist (Scarface, The Public Enemy, Little Caesar in the 1930s through to, say, Dead Presidents in the 1990s) pursued individual wealth and personal success but because of race/ethnic/class exclusion had to rely on ‘illegitimate’ means. In the 1940s, with High Sierra and Force of Evil there is a shift to depicting organised crime as not really any different from capitalist corporations – a tendency which reaches a high point in especially the second Godfather film, and which results in bankers becoming indistinguishable from criminals in The International. Against that genre history, The Long Good Friday takes on a British neoliberal – or Thatcherite – specificity in the way it maps out relations between between crime, politics, policing, urban redevelopment and international finance. Gangland boss Harold Shand (Bob Hoskins) captures something of the Conservative’s ideological contradiction between

- a there-is-no-such-thing-as-society neoliberalism of competitive economic self-interest and ‘freedom’

- a social conservatism (family, nation, social order, white privilege, etc)

The depiction of the Irish and especially the IRA is informative in this regard. The film came out as the Conservative government and their media lackeys were changing the treatment and representation of the IRA from political dissidents to nothing more than a violent criminal gang. This process began much earlier but had a particular resonance at the time – the film was released on 2 February 1981, less than a month before Bobby Sands and others began the second hunger strike in the Maze Prison. The film also sees politics and political commitment treated as an utterly inexplicable black box, and self-serving economic competition as natural, normal common-sense everyone understands and agrees with – a straight-up Thatcher move (that also involves pretending neoliberalism is not a political project, and accelerating the transition, that Adorno and Horkheimer wrote about years earlier, from government to governance).

We also thought about the film’s treatment of urban gay culture – on the one hand, a little bit seedy and secretive; on the other, everyone knows but no one much cares that Colin (Paul Freeman), Shand’s right-hand man, is gay; on the third hand, if you are gay in this movie you do die violently.

The representation of Brixton is also marked by contradictions: multi-ethnic streets (including a baby Dexter Fletcher!), but Shand implies that it is a black neighbourhood and that is why it has gone downhill; he also expresses disbelief at people being forced to live in such conditions, but it is not entirely clear whether this is empathy or a wannabe property developer seeing an opportunity – not an opportunity to build regular folks better homes, but an opportunity to get rich from property speculation.

London’s Overthrow

The Long Good Friday‘s unredeveloped docklands setting and the anticipation of a 1988 London Olympics make it increasingly timely – and a good match for Miéville’s essay. London’s Overthrow was written partly as a response to the propaganda surrounding the London Olympics development, and in the long shadow cast by the police killing of Mark Duggan and the popular protests (or ‘riots’) that swept British cities 6-11 August 2011.

Sadly, all the Olympics promos I could find online contained some airbrushed images of London but focused much more on athletes doing athletics – understandable, if unhelpful in this context. So we took a look at this short London tourism video from 2014 – all iconic architecture, tradition and (financial) modernity, almost entirely North of the Thames, bustling but never crowded, multi-ethnic but quite astonishingly white-looking, prettified. (Frankly, this video is more fun, especially the way it cons you into outrage at seeming to miss the entire point of The Clash, but I am still not sure what to make of this one.)

We didn’t have enough time to do more than some headline points about Miéville’s essay:

- the publicity image of London contrasted with apocalyptic imagery;

- the publicity image of London contrasted with imagery of a more diverse and stratified London;

- the city transformed by technologies: the phone camera, advertising and other screens;

- the city transformed by ownership: public space, privatised spaces, ASBOs (PSPOs);

- planned London and unplanned London;

- and, because there is something delightfully wrong about mentioning Jacques Derrida in the first week of an undergraduate degree, controlling the future (l’futur) and leaving potentials open (l’avenir)

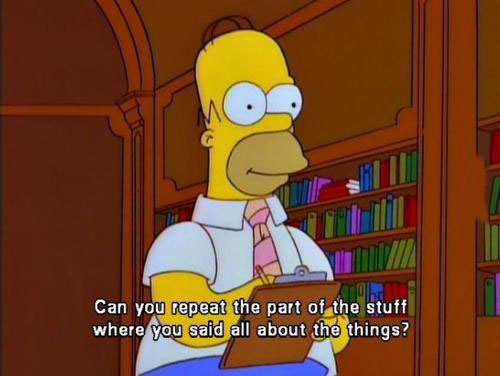

If there were world enough and time, it would have been good to contrast some of the youtube footage of the 1985 Broadwater Farm uprising with Wretch 32’s ‘Unorthodox’ video that Miéville discusses. But as it was, there was barely time even to conclude with this image:

From the too-much-information section of the module handbook:

Recommended reading

China Miéville’s novels are usually set in an alternative London (King Rat (1998), Un Lun Dun (2007), Kraken (2010)), or in one of the cities in the fantasy world of Bas Lag (Perdido Street Station (2000), The Scar (2002), Iron Council (2004)). The City & the City (2009) is a murder-mystery set in two different cities that occupy the same physical space.

Elizabeth Bowen’s “Mysterious Kôr” (1944) contrasts an imaginary city with wartime London as an unmarried couple try to find somewhere they can sleep together.

This concern with the relationships between real and unreal cities is also central to Arthur Machen’s The Three Impostors (1895), Alasdair Gray’s Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981), Megan Lindholm’s Wizard of the Pigeons (1985), Iain Banks’s The Bridge (1986), Karen Tei Yamashita’s Tropic of Orange (1997), G. Willow Wilson’s Cairo (2007) and David Eggers’s A Hologram for the King (2012).

Recommended viewing

Other movies about the murky connections between crime, business and politics include The Bad Sleep Well (Kurosawa 1960), Get Carter (Hodges 1971), The Godfather (Coppola 1972), Chinatown (Polanski 1974), The Godfather: Part II (Coppola 1974), City of Hope (Sayles 1991), Face (Bird 1997), The Baader-Meinhof Complex (Edel 2008), Mesrine (Richet 2008) and The International (Tykwer 2009).

Julien Temple’s documentary London: The Modern Babylon (2012) offers a history of the city through found footage – taken from films, newsreels, television, etc – that is useful for thinking about the ways in which moving images shape our understanding, expectations and memories of cities. Thom Andersen’s documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) uses movie footage to explore the ways in which Los Angeles is represented (and represents other cities) in Hollywood films – and to contrast this virtual or imaginary ‘Los Angeles’ with his own experience of living in the ‘real’ Los Angeles. Guy Maddin’s pseudo-documentary My Winnipeg (2007) concocts a fictional history of his hometown.

Sounds great, Mark. Please carry on blogging about this!

S

LikeLike