[After finding yesterday’s old piece on China, I remembered doing this one, too. But on reading it, I have no memory at all of writing it. It’s from the Readercon 17 programme, back in 2006 when China and James Morrow were GoHs.]

This was the plan, the plan was this: I would get the first post-rush hour train from Bristol to London and be there by noon.

‘There’ is the Starbucks in Borders bookstore on Oxford Street, our default meeting-up place in central London, and we would leave ‘there’ as soon as possible, and grab some pizza at a place around the corner (where, a year earlier, our arrival had been greeted with rapturous applause from the staff – not because they recognised China, but because they’d been open for almost an hour and we were their first customers that day). And after lunch, although the pretext for meeting up was discussing essay proposals for a book we are editing on Marxism and sf, we would head to the Natural History Museum to see the thirty-foot long, newly-on-display, giant squid.

‘There’ is the Starbucks in Borders bookstore on Oxford Street, our default meeting-up place in central London, and we would leave ‘there’ as soon as possible, and grab some pizza at a place around the corner (where, a year earlier, our arrival had been greeted with rapturous applause from the staff – not because they recognised China, but because they’d been open for almost an hour and we were their first customers that day). And after lunch, although the pretext for meeting up was discussing essay proposals for a book we are editing on Marxism and sf, we would head to the Natural History Museum to see the thirty-foot long, newly-on-display, giant squid.

That was the plan, the plan was that.

So of course that was not what happened.

Readers of King Rat and the stories in Looking for Jake (and a forthcoming project, as yet still a secret [Un Lun Dun, I guess]) will know that London is a strange place, where all kinds of unexpected things can happen; that the fabric of the city itself is fantastical. Strange chimera flit through the crowds, pausing to take fliers advertising clubs and bars and language schools from fastidiously scruffy young men and women being paid way less than minimum wage for their cash-in-hand labour, and roar in anguish, in bafflement, at this world which is no longer theirs, and retreat temporarily into the interstices, before emerging once more, hooked on it. Creatures, remnants from another time, can be glimpsed in the reflective surfaces of department stores and sandwich shops, phone booths and passing buses. Others dance across the rooftops. And then there’s the people, who are pretty fucking strange.

But our delays and derailments are far more mundane. Family. Trains. And by the time we get ‘there’ it is gone two o’clock. (There was an amusing incident involving a borrowed phone in case China needed to contact me, which he does, but by text, which my quick briefing on this new-fangled technology did not cover. I manage to find the message but am uncertain how to reply. I amaze myself by finding China’s number in the phone’s address book, so I call and leave him a message. The number later transpires to be that of his old phone. But I will omit this is at makes me sound much too old yet insufficiently curmudgeonly. And has nothing to do with trains or cephalapods.)

Lunch is relocated to an Italian restaurant, which does a pasta dish China likes involving little balls of fried courgette and spinach. Our arrival prompts neither adulation nor irony.

‘Trains,’ I tut, to boost my curmudgeon-score as we share a mezze and several varieties of bread. But we have been talking about trains a lot, lately. I have a crazy notion that there is a book to be written about trains and early cinema and time-travel (but very distinctly not about early railroad films or time-travel movies), and China’s voracious reading, especially the research for Iron Council (and for his review of Stefan Grabinski’s The Motion Demon), keeps throwing up gems. It’s like having a really good research assistant I don’t have to supervise or pay (although he has still not returned my copies of The Iron Horse, Once Upon a Time in the West and Emperor of the North Pole).

‘Trains,’ I tut, to boost my curmudgeon-score as we share a mezze and several varieties of bread. But we have been talking about trains a lot, lately. I have a crazy notion that there is a book to be written about trains and early cinema and time-travel (but very distinctly not about early railroad films or time-travel movies), and China’s voracious reading, especially the research for Iron Council (and for his review of Stefan Grabinski’s The Motion Demon), keeps throwing up gems. It’s like having a really good research assistant I don’t have to supervise or pay (although he has still not returned my copies of The Iron Horse, Once Upon a Time in the West and Emperor of the North Pole).

These are the three things he tells me.

‘The seemingly obvious use of the railroad to “mean” Manifest Destiny, as in Zane Grey’s The U.P. Trail, is only permissible because of the peculiarity of that particular railroad. It really did only have one line, at least for a brief moment, but much longer iconically, and that’s been the source of a lot of notions of the unilinearity of the railroad, which are completely spurious. Not even a consideration of the siding or even the parallelism of tracks (necessary unless all trains are going only one way, a patent absurdity). So railroads aren’t even a misused symbol – they only work symbolically because of a lie.’

‘Of a failure, no, a refusal, to observe accurately,’ I suggest, ‘because that would strip the metaphor of its political potency.’

The mezze is really good.

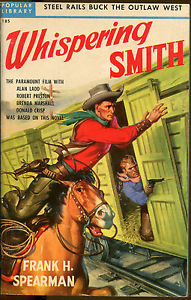

‘Iron Council riffed heavily on Frank Spearman’s Whispering Smith. Spearman was a sort-of libertarian, reportedly Ayn Rand’s favourite writer, did lots of stuff about rugged railwaymen. Whispering Smith is a troubleshooter for the railroad who is allowed to go anywhere and do more or less anything, including kill anyone necessary, to “fix problems”. It is an extremely perspicacious critique of rugged individualist/libertarian railroadism (as I’ve christened the ideology), because contrary to the “enlightened self-interest” of the Randists and half of Spearman’s own characters, the thrusting of the rails is only possible with a roving assassin – a man in a permanent state of Schmittian law-making exception! – bringing peace for capital-expansion at the end of a gun beyond the bounds of the rails. So the railroad relies for the always-spurious solidity of even its semiotic status to the right on an implicit awareness of beyond-railroad coercion of the most violent kind. Spearman, a cunning writer, recognises this and rather than attempt to conceal it, hides its in plain view.’

‘Iron Council riffed heavily on Frank Spearman’s Whispering Smith. Spearman was a sort-of libertarian, reportedly Ayn Rand’s favourite writer, did lots of stuff about rugged railwaymen. Whispering Smith is a troubleshooter for the railroad who is allowed to go anywhere and do more or less anything, including kill anyone necessary, to “fix problems”. It is an extremely perspicacious critique of rugged individualist/libertarian railroadism (as I’ve christened the ideology), because contrary to the “enlightened self-interest” of the Randists and half of Spearman’s own characters, the thrusting of the rails is only possible with a roving assassin – a man in a permanent state of Schmittian law-making exception! – bringing peace for capital-expansion at the end of a gun beyond the bounds of the rails. So the railroad relies for the always-spurious solidity of even its semiotic status to the right on an implicit awareness of beyond-railroad coercion of the most violent kind. Spearman, a cunning writer, recognises this and rather than attempt to conceal it, hides its in plain view.’

‘Agamben,’ I mutter, sipping a rather non-descript red wine, knowing that his Schmitt reference is more astute than my name-drop (but then he did study – and write a book on – legal theory). I refill my glass and reflect on how it is possible for China to talk so enthusiastically about stuff despite his rather non-committal approach to drinking.

‘And then there’s Bruno Schulz, using trains (in several different ways – history as both inside and outside the train itself, on the rails as well as in the corridors) to think about the alterity of history and alternate possibilities. I’m increasingly interested by the idea of the multi-track nature of railroads, let alone Grabinski’s sidings, as key to their importance. There’s this astonishing passage in his ‘The Age of Genius’ in The Sanitorium under the Sign of the Hourglass:

‘And then there’s Bruno Schulz, using trains (in several different ways – history as both inside and outside the train itself, on the rails as well as in the corridors) to think about the alterity of history and alternate possibilities. I’m increasingly interested by the idea of the multi-track nature of railroads, let alone Grabinski’s sidings, as key to their importance. There’s this astonishing passage in his ‘The Age of Genius’ in The Sanitorium under the Sign of the Hourglass:

Ordinary facts are arranged within time, strung along its length as on a thread. There they have their antecedents and their consequences, which crowd tightly together and press hard one upon the other without any pause. This has its importance for any narrative, of which continuity and successiveness are the soul.

Yet what is to be done with events that have no place of their own in time; events that have occurred too late, after the whole of time has been distributed, divided and allotted; events that have been left in the cold, unregistered, hanging in the air, homeless and errant?

Could it be that time is too narrow for all events? Could it happen that all the seats within time might have been sold? Worried, we run along the train of events, preparing ourselves for the journey.

For heaven’s sake, is there perhaps some kind of bidding for time? Conductor, where are you?

Don’t let’s get excited. Don’t let’s panic; we can settle it all calmly within our own terms of reference. Have you ever heard of parallel streams of time within a two-track time? Yes, there are such branch lines of time, somewhat illegal and suspect, but when, like us, one is burdened with contraband of supernumerary events which cannot be registered, one cannot be too fussy. Let us try to find at some point of history such a branch line, a blind track onto which to shunt these illegal events. There is nothing to fear. It will all happen imperceptibly: the reader won’t feel any shock. Who knows? Perhaps even now, while we mention it, the doubtful manoeuvre is already behind us and we are, in fact, proceeding into a cul-de-sac.

‘Isn’t that fucking amazing?”

I have to agree.

I also have to confess.

This was the plan, the plan was this: over lunch we would talk wisely and wittily about arcane things, scare the children at the next table with our profanity and their parents with out erudition (or vice versa). It is not that China is scarily geeky (although he does know his shit), nor that I cannot write convincing dialogue (although I cannot); but rather that China’s words come from a long and almost painfully helpful email he sent me after a phone conversation about matters locomotive.

Conversation over lunch that day really focused on our childish enthusiasm for all things cephalopodic and tentacular. I’d recently rewatched Jon Lurie’s series of fake fishing documentaries, Fishing With John, in which he takes various celebrities – Jim Jarmusch, Tom Waits, Matt Dillon, Willem Dafoe – on improbable fishing expeditions. The series ends with a two-parter in which John – who died while ice-fishing with Willem in the previous instalment, a fitting punishment considering they used the proper equipment rather than chainsaws to cut through the ice – is discovered to be not only alive and well but taking Dennis Hopper fishing for giant squid in the Andaman Sea. After arduous travels, unsuccessful angling, a sidetrip to see some squid-worshipping monks who warn of the giant squid’s hypnotic powers, they finally meet with success, of a sort. A giant squid rises to the surface. But all is not well. Disorientation strikes Dennis and John. What is going on? Has something happened? They leave Asia disconsolate, because despite seeing their prey up close, it hypnotised them, and they believe their expedition a complete failure.

Jeff VanderMeer’s name of course crops up, as it always does in squidversations. But a new potential source of delight is introduced. An aside about James Woods not sleepwalking through a performance but actually sleeping through a performance in ER triggers a memory deep in China.

‘Have you ever,’ he asked, ‘seen Tentacles? I’ve only heard about it – a 70s Jaws rip-off about a giant octopus – in which John Huston literally phones in his performance. Apparently, he finally gave in and agreed to appear in it on the condition that he didn’t have to leave his own home to do so. So his performance consists of him sitting on a lawn-chair on his own lawn, saying things over his own phone like, “Hmmm, yes, that does sound like it could be the work of a giant octopus”.’

Neither wise nor witty, neither arcane nor profane; more geeky than erudite; but it certainly did scare the children sat at the table next to us. And their parents.

***

Coda 1. We did actually discuss the proposals and finalise the line-up for Red Planets: Marxism and Science Fiction.

Coda 2. The little balls of courgette and spinach are really rather good.

Coda 3. While China’s books are available at all good bookstores, it is worth noting that Tentacles is also available on region 1 DVD, but while I was able to pick up a copy for just five bucks, there is a heavy price to pay: it comes with the Joan Collins movie Empire of the Ants, a low point in a career hardly distinguished by its heights.

Coda 4. We never did get to the Natural History Museum to see the giant squid.

Coda 5. Unless we did but just can’t remember. Hypnotic powers, y’know.