[This is one of several pieces written for a book on adaptations that has never appeared]

Maurice Renard’s Les Mains d’Orlac/The Hands of Orlac (1920), adapted as Orlacs Hände (Robert Wiene 1924), Mad Love (Karl Freund 1935) and The Hands of Orlac aka Hands of the Strangler (Edmond T. Gréville 1960)

A mad scientist replaces the badly injured hands of a concert pianist with those of a recently executed murderer, but the hands possess the pianist, turning him into a killer. As this typical, but inaccurate, synopsis suggests, The Hands of Orlac is one of those stories that everyone thinks they know but few actually do. This is not inappropriate, since Renard’s novel, and to a lesser extent its adaptations, are structured around the (mis)interpretation of events and the actions that flow from partial or mistaken knowledge.

The novel is the most difficult of the variants to synopsise. This is not because it is necessarily more intricate and nuanced than any of the adaptations – which would be hard to judge anyway. Maurice Renard is an infrequently and poorly translated author,[1] and neither of the translations of Les Mains d’Orlac (Florence Crewe-Jones (1929), Iain White (1981)) have a particularly good reputation. Orlacs Hände exists only in a truncated version, about 150 metres (two minutes) having been lost. After Mad Love’s initial release, MGM cut fifteen minutes of footage, including Isabel Jewell’s entire performance, which seems to have been lost. According to most sources, The Hands of Orlac, was released in France with a runtime of 104 minutes and in the UK of 95 minutes; there is also a US cut of 84 minutes, from which Donald Pleasance’s single scene as a sculptor is absent, although his name appears in the credits, and in which the admittedly brief performance of Sir Donald Wolfit as Orlac’s surgeon is reduced to a single line of dialogue. (I will discuss the English cut, but make some reference to a slightly longer French-language version which appears on the Spanish DVD and whose existence casts some doubt on whether there was ever a version as long as 104 minutes).

The novel is the most difficult of the variants to synopsise. This is not because it is necessarily more intricate and nuanced than any of the adaptations – which would be hard to judge anyway. Maurice Renard is an infrequently and poorly translated author,[1] and neither of the translations of Les Mains d’Orlac (Florence Crewe-Jones (1929), Iain White (1981)) have a particularly good reputation. Orlacs Hände exists only in a truncated version, about 150 metres (two minutes) having been lost. After Mad Love’s initial release, MGM cut fifteen minutes of footage, including Isabel Jewell’s entire performance, which seems to have been lost. According to most sources, The Hands of Orlac, was released in France with a runtime of 104 minutes and in the UK of 95 minutes; there is also a US cut of 84 minutes, from which Donald Pleasance’s single scene as a sculptor is absent, although his name appears in the credits, and in which the admittedly brief performance of Sir Donald Wolfit as Orlac’s surgeon is reduced to a single line of dialogue. (I will discuss the English cut, but make some reference to a slightly longer French-language version which appears on the Spanish DVD and whose existence casts some doubt on whether there was ever a version as long as 104 minutes).

The difficulty of synopsising the novel arises from the nature of its composition and initial publication as a feuilleton in 58 daily instalments in the mass-circulation Parisian evening newspaper, L’Intransigeant (May 15–July 12, 1920). It was not uncommon for feuilletonists to write at great speed, and for instalments to appear within days or even hours. This often produced an improvisational style of fiction into which characters, events and ideas were mixed without the consequences necessarily being fully worked out, generating contradictions to be reconciled and loose ends to be tied up (or not). The Surrealists considered such frequently dreamlike fiction as a kind of automatic writing, especially when it was bizarre, fantastic or mysterious, or evoked Freudian themes (although there seems to be no connection between Mad Love and André Breton’s L’Amour fou (1937)).

Renard is little known to Anglophone readers, but ‘most European and French-Canadian sf scholars hold’ his work ‘in very high esteem’, and he has been described as the most important French sf writer of the first third of the twentieth century (Evans 380). Despite its pulpiness, Les Mains d’Orlac – with its play on perception and perspective, its self-reflexiveness about mass media and its shock-of-modernity concern with industrial catastrophe, dismemberment, somnambulism, automatism and the externalisation of the self through such semiotic technologies as handwriting, fingerprinting, typewriters and gramophones – should be considered alongside works by Daniel Paul Schreber, Winsor McCay, Stefan Grabiński and Bruno Schulz in terms of its ability to capture something of the phantasmagorical nature of life in capitalist-industrial modernity. Indeed, it is unsurprising to find Friedrich A. Kittler fascinated by Renard’s ‘Death and the Shell’ (1907), which he describes as a ‘constellation’ of ‘phonography, notation, and a new eroticism’ (51) and as the first in ‘a long series of literary phantasms that rewrite eroticism itself under the conditions of gramophony and telephony’ (56).

Les Mains d’Orlac opens with a preamble in which the narrator excuses the novel’s artless construction, although the limited perspective – it is mostly told from Madame Rosine Orlac’s viewpoint and in strict chronological order – is absolutely essential to the effectiveness with which the reader is placed in a position of uncertainty about the nature of the events described. Are they supernatural or the product of sinister human agents? Is Rosine hallucinating, her reason becoming unhinged?

Awaiting her husband’s return from a concert in Nice, Rosine is filled with foreboding. His train crashes, killing many. Rosine finally finds him, buried beneath a corpse in the wreckage, with a fractured skull and other injuries. She races him back to Paris so that he can be treated by the famous Doctor Cerral. Athough she is warned that there is something unsavoury about Cerral, he appears to her as a kind of superhuman figure, saving Stephen’s life and apparently restoring his mangled hands. However, as Stephen convalesces, Rosine grows increasingly troubled. Since the night of the crash she has been haunted by a phantasm, whom she dubs Spectropheles. Anxious about Stephen’s restless sleep, she enters his room and sees one of his nightmares externalised, a montage of images floating in the air: Stephen’s hands are poised over a piano from which he draws a knife with an X carved in its handle; blood drips from the blade; the blade becomes that of a guillotine hanging over his head…

Stephen became a pianist against his father’s wishes. Subsequently, Edouard Orlac has refused to have anything to do with him and has fallen increasingly under the sway of his servants, Crépin and Hermance. His obsession with spiritualism is shared with Monsieur de Crochans, an impoverished artist who once had the potential to become a successful portraitist but instead turned to decadence, impressionism, and now ‘“psychic painting’ … ‘“portraits of souls” and “mental landscapes”’ (Renard 1981, 44). de Crochans, who has slowly been effecting a reconciliation between father and son, becomes Rosine’s confidant, explaining away the externalised nightmare as ‘Ideoplasty! … a fragmentary apparition of his astral body, that phantasm of the living’ (74).

When Stephen is finally well enough to be brought home, they arrive to find an X-handled knife stuck in their apartment door (Rosine also sees Spectropheles). Already distraught, Stephen becomes increasingly depressed at his inability to play the piano. Cerral recommends courses of ‘massage, gymnastics, electrotherapy’ (90), as much for their psychological effect as for any likely success in making Stephen’s hands sufficiently flexible and dextrous to return to his career. Stephen adopts such treatments with a mania, and Rosine keeps to herself how deeply he is digging into their limited finances. It soon reaches the point when she must sell her jewels, but when she opens her locked jewel-box, they are missing, replaced by the calling card of La Bande Infra-Rouge. Is there a connection with Spectropheles? Does the X on the knife handles signal X-Rays? Is the Infra-red gang somehow using an invisible part of the spectrum to move through solids and get past locks? Rosine doubts her fevered hypotheses, but becomes increasingly anxious about their share certificates, whose value is plummeting due to a market slump. One night she intrudes upon a burglar (who cannot possibly be in their apartment), only to find that certificates safe and the jewels returned.

When Stephen is finally well enough to be brought home, they arrive to find an X-handled knife stuck in their apartment door (Rosine also sees Spectropheles). Already distraught, Stephen becomes increasingly depressed at his inability to play the piano. Cerral recommends courses of ‘massage, gymnastics, electrotherapy’ (90), as much for their psychological effect as for any likely success in making Stephen’s hands sufficiently flexible and dextrous to return to his career. Stephen adopts such treatments with a mania, and Rosine keeps to herself how deeply he is digging into their limited finances. It soon reaches the point when she must sell her jewels, but when she opens her locked jewel-box, they are missing, replaced by the calling card of La Bande Infra-Rouge. Is there a connection with Spectropheles? Does the X on the knife handles signal X-Rays? Is the Infra-red gang somehow using an invisible part of the spectrum to move through solids and get past locks? Rosine doubts her fevered hypotheses, but becomes increasingly anxious about their share certificates, whose value is plummeting due to a market slump. One night she intrudes upon a burglar (who cannot possibly be in their apartment), only to find that certificates safe and the jewels returned.

Rosine discovers that Stephen has found more X-handled knives (which, when distressed, he throws into his studio door) and been receiving notes from La Bande Infra-Rouge, telling him that ‘The TEN … require blood’ (164). Does the X stand for ten? Are there ten members of the gang? Rosine conspires with de Crochans to speed Stephen and Edouard’s reconciliation by getting him to take an interest in spiritualism, and de Crochans decides to try to work a kind of psychoanalytical cure, using the tricks of fake mediums to dig into Stephen’s subconscious mind. On the eve of what he feels will be his certain success, de Crochans is murdered, apparently strangled by a life-size artist’s dummy into which he and Stephen had been summoning the spirits of murderers. The crime-reporter, Gaston Breteuil, who ostensibly narrates the novel, becomes Rosine’s new confidant.

Financial ruin looms. Stephen goes to beg for Edouard’s help, only to find him murdered with an X-handled knife. Inspector Cointre recognises the X-shaped wounds, made by plunging the knife in twice, as the work of Vasseur, a recently guillotined multiple murderer whose fingerprints are on the knife. Apparently, when Vasseur had been summoned during a séance, his luminous, knife-wielding hand killed Edouard, but Cointre suspects the fingerprints were planted there from a moulding on a rubber glove. Mysteriously, the calling card of La Bande Infra-Rouge is found in Edouard’s strongbox.

Financial ruin looms. Stephen goes to beg for Edouard’s help, only to find him murdered with an X-handled knife. Inspector Cointre recognises the X-shaped wounds, made by plunging the knife in twice, as the work of Vasseur, a recently guillotined multiple murderer whose fingerprints are on the knife. Apparently, when Vasseur had been summoned during a séance, his luminous, knife-wielding hand killed Edouard, but Cointre suspects the fingerprints were planted there from a moulding on a rubber glove. Mysteriously, the calling card of La Bande Infra-Rouge is found in Edouard’s strongbox.

A stranger accosts Stephen, describing how Cerral had obtained the body of Vasseur fresh from the guillotine and transplanted his hands onto Stephen (who has known this for some time). The stranger describes how he has been manipulating Stephen: the externalised nightmare was a cinematographic projection; the Orlacs’ maid, Régina, has been planting the knives and messages, as well as using Stephen’s typewriter to produce notes that will incriminate him in his father’s murder. The stranger wants a million francs from Stephen’s inheritance to not reveal his ‘guilt’ – and as a payment for his hands. He claims to be Vasseur, his head reattached by Cerral’s assistant and his hands replaced with the crude metal prosthetics that crushed the life from de Crochans. Stephen agrees to pay up in exchange for the gloves with Vasseur’s moulded fingerprints.

Stephen tells Rosine everything, and between them they manage to explain away all the mysterious goings on – for example, Stephen took the jewels so that he could secretly get his rings enlarged to fit his new hands – except for the appearances of Spectropheles (who she finally decides is an intermittently appearing form of scotomy, the image left on the retina after staring at a bright object). Rosine insists that they inform the police so that Vasseur can be recaptured, but when he is, he is revealed to be the criminal Eusebio Nera. Cointre realises that the rubber glove is at least two years old, which means that Vasseur was executed for murders he did not commit and that Stephen’s ‘hands are undefiled’ (301).

Stephen tells Rosine everything, and between them they manage to explain away all the mysterious goings on – for example, Stephen took the jewels so that he could secretly get his rings enlarged to fit his new hands – except for the appearances of Spectropheles (who she finally decides is an intermittently appearing form of scotomy, the image left on the retina after staring at a bright object). Rosine insists that they inform the police so that Vasseur can be recaptured, but when he is, he is revealed to be the criminal Eusebio Nera. Cointre realises that the rubber glove is at least two years old, which means that Vasseur was executed for murders he did not commit and that Stephen’s ‘hands are undefiled’ (301).

Even such a lengthy synopsis omits much of the concatenated material that gives the novel its distinctive texture – as do the adaptations. Orlacs Hände shifts the narrative focus away from Yvonne (as Rosine is renamed) and onto Paul (as Stephen is renamed). However, it does not do so until after she has recovered his mangled body from the train wreck. Wolfgang Schivelbusch describes the train crash as the exemplary experience of an industrial modernity that frequently renders the human body vulnerable by placing it in an environment of mass and speed. David J. Skal argues that the obsession with mutilation and amputation in horror movies of the 1920s and 1930s articulates the increased incidence, presence and visibility of such damaged bodies after World War One. The extraordinary first section of Renard’s novel – with its emphasis on speed, collision, dismemberment, agglomeration, confusion, the desubjectivation of corpses, the intermingling of the living and the dead – conjoins the battlefield with the everyday experience of modernity. Although Wiene’s film simplifies the action, it achieves a similar effect: Yvonne’s car races through a pitch-black night, its headlights making little impression on the darkness pooled around it, while the flaring of other lights add to the apocalyptic depiction of the wreckage, obscured by night, clouds of steam and milling crowds, which culminates in a diegetic spotlight that scans back and forth across the devastation becoming eye-like when pointing directly at the camera.

The shift of focus onto Paul transforms the film into a star vehicle for Conrad Veidt (Wiene had already directed him in two remarkable performances as a gaunt Indian priest and the somnambulist Cesare in, respectively, the little-remembered Furcht (1917) and the Expressionist masterpiece, Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920)). Consequently, numerous  incidents, including all the business with spiritualism and La Bande Infra-Rouge, and certain characters, including de Crochans, Hermance and Breteuil, were dropped, while Cerral becomes a genial, middle-aged man and the treachery of the maid, now called Regine, is revealed earlier and partially redeemed. The relationship between Paul and his father is reduced to a scene in which Yvonne begs from an aloof and monstrous figure who utterly rejects her pleas. Key incidents are reworked into single shots: rather than the jewel-theft shenanigans, Paul merely tries to put on his now-too-small wedding ring; the scene in which Rosine thinks she hears Stephen playing the piano, only to find him listening to a recording of an earlier performance, is replaced by one in which Paul briefly torments himself with the recording before smashing it. The externalised nightmare, retained so as to take advantage of its eerie spectacle, takes a rather different form. When Yvonne is trying to comfort Paul, he has a vision in which a head seems to be floating in mid-air – although it might just be someone looking in through the transom – but she sees nothing. Later, he has a nightmare about it. In a side-on long-shot, his bed is positioned in the lower left corner of the frame, suggesting the isolation and diminution of this once impressive figure. In the top right quadrant of the screen a cloud coalesces into the same disembodied head, giant-sized, and an enormous clenched fist reaches down diagonally across the screen towards the sleeping Paul, who wakes up screaming and finds a note telling him that he has been given the ‘hands of the executed robber and murderer Vasseur!’ (underlining in the original). The nightmare is externalised, but only for the audience, and as in the novel, it is done so through cinematic trickery.

incidents, including all the business with spiritualism and La Bande Infra-Rouge, and certain characters, including de Crochans, Hermance and Breteuil, were dropped, while Cerral becomes a genial, middle-aged man and the treachery of the maid, now called Regine, is revealed earlier and partially redeemed. The relationship between Paul and his father is reduced to a scene in which Yvonne begs from an aloof and monstrous figure who utterly rejects her pleas. Key incidents are reworked into single shots: rather than the jewel-theft shenanigans, Paul merely tries to put on his now-too-small wedding ring; the scene in which Rosine thinks she hears Stephen playing the piano, only to find him listening to a recording of an earlier performance, is replaced by one in which Paul briefly torments himself with the recording before smashing it. The externalised nightmare, retained so as to take advantage of its eerie spectacle, takes a rather different form. When Yvonne is trying to comfort Paul, he has a vision in which a head seems to be floating in mid-air – although it might just be someone looking in through the transom – but she sees nothing. Later, he has a nightmare about it. In a side-on long-shot, his bed is positioned in the lower left corner of the frame, suggesting the isolation and diminution of this once impressive figure. In the top right quadrant of the screen a cloud coalesces into the same disembodied head, giant-sized, and an enormous clenched fist reaches down diagonally across the screen towards the sleeping Paul, who wakes up screaming and finds a note telling him that he has been given the ‘hands of the executed robber and murderer Vasseur!’ (underlining in the original). The nightmare is externalised, but only for the audience, and as in the novel, it is done so through cinematic trickery.

Renard makes a couple of references to sleepwalking and frequently evokes the idea of automata, including a single-paragraph ‘mnemonic mirage’ (215) which alludes to the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann (1816), Prosper Mérimée’s ‘La Vénus d’Ille’ (1837), Villiers de L’Isle-Adam’s L’Ève future (1886), Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka (1911) and real-life automata-makers Jacques de Vaucanson and Johann Nepomuk Mälzel. For Renard, the image of mechanized being is part of a broader critique of capitalist-industrial modernity which, to paraphrase Marx, makes subjects out of things and things out of subjects. This is emphasised when, on the morning after the crash, a broker arrives for an appointment to insure Stephen’s hands, just a few hours too late to do any good. In a similarly ironic vein, the Orlacs’ money always runs out at a slightly faster rate than Stephen’s hands recover, and a temporary slump in the market randomly devalues their property. Furthermore, in a proto-Frankfurt School critique of the culture industry, characters repeatedly compare their own actions and responses to those characters in fiction and film – at one point de Crochans begins to pat Rosine’s shoulder to comfort her, but just in time ‘he recalled that cinema actors never neglect the realistic detail … and, out of bashfulness, he ceased’ (60) – and at moments of heightened tension Rosine is often at least half-aware that she is struggling not to interpret fantastical events in the terms provided by pulp fictions and cinematic thrillers. Against a backdrop of such overdetermining powers, the living seem little different to the broken dead; and the hysterical pitch of Rosine’s narrative comes across as a frantic denial of such a reduction of human agency. Orlacs Hände displaces much of this critical potential onto its Expressionist aesthetics. Wiene utilises cavernous sets, often in long-shot, that are pooled in darkness and almost devoid of furniture apart from the occasional oddly diminished item. Other sets, dominated by statues or giant urns, resemble sketches of generic places, as if greater verisimilitude would distract from the inner turmoil of the characters. Indeed, some close-ups and medium shots eschew any background at all, the actor’s faces and torsos appearing against black backdrops. In one notable shot, Yvonne sits on a chair facing the camera, while standing behind her in a row are four more-or-less indistinguishable creditors, motionless apart from choreographed shakes of the head which refuse her requests for more time. Wiene’s paring down of mimetic places to abstract spaces dotted with signifiers creates a sense of puppet theatre, at the centre of which is Veidt’s performance.

While some of his close-ups and medium-shots might seem overwrought by more contemporary conventions, Veidt remains compelling as a physical actor. When Paul wakes from his nightmare, his hands seem to take on a life of their own; and later, when he is agitated and impatient, they spasm and begin to play on tabletops as if they were keyboards, apparently without him commanding or even noticing them. When Paul goes to confront Serral (as Cerral is renamed), Veidt holds his arms extended, fingers splayed, his slightly shortened sleeves exposing hands that he is either pushing away from himself or being towed behind. His carriage often embodies the novel’s idea of a mannequin possessed by the spirit of a dead man. At several points, his body shrinks into a hollow inertia, an enfeebled appendage to his determined hands, which drag him around as if they are the only part of a puppet still held up by strings. Lotte H. Eisner describes his performance as ‘a kind of Expressionist ballet, bending and twisting extravagantly, [in which he is] simultaneously drawn and repelled by the murderous dagger held by hands which do not seem to belong to him’ (145), and as if to confirm its Expressionist credentials, in one shot, while the police investigate the scene of Orlac’s father’s murder, Veidt raises his hands to either side of his contorted face, the very image of Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893–1910).

While some of his close-ups and medium-shots might seem overwrought by more contemporary conventions, Veidt remains compelling as a physical actor. When Paul wakes from his nightmare, his hands seem to take on a life of their own; and later, when he is agitated and impatient, they spasm and begin to play on tabletops as if they were keyboards, apparently without him commanding or even noticing them. When Paul goes to confront Serral (as Cerral is renamed), Veidt holds his arms extended, fingers splayed, his slightly shortened sleeves exposing hands that he is either pushing away from himself or being towed behind. His carriage often embodies the novel’s idea of a mannequin possessed by the spirit of a dead man. At several points, his body shrinks into a hollow inertia, an enfeebled appendage to his determined hands, which drag him around as if they are the only part of a puppet still held up by strings. Lotte H. Eisner describes his performance as ‘a kind of Expressionist ballet, bending and twisting extravagantly, [in which he is] simultaneously drawn and repelled by the murderous dagger held by hands which do not seem to belong to him’ (145), and as if to confirm its Expressionist credentials, in one shot, while the police investigate the scene of Orlac’s father’s murder, Veidt raises his hands to either side of his contorted face, the very image of Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893–1910).

Through its relative displacement of the economic and social determinants evident in the novel, Orlacs Hände emphasises – and radically transforms – Orlac’s psychosexual compulsions. Bubbling away in Les Mains d’Orlac is an anxiety about masturbation every bit as strong as that of the Dr. Seuss-scripted The 5,0000 Fingers of Dr. T (Rowland 1953). Rosine, who is sleeping in the room next to the convalescing Stephen, is ‘awakened by an agonised gasp’, listens ‘to the sleeper tossing and turning; and groaning … an unpleasant sound’, feels ‘a hateful sensation of wretchedness and defeat’ as she hears him ‘uttering muffled cries; and then … a hoarse, headlong, agitated breathing’ and then finds him ‘kneeling on his bed in an attitude of prostration’ (70–71). Once they are back at their apartment, he spends hours alone in his room, poring in secret over imported literature, obsessing over his hands with mysterious unguents and mechanisms, even sneaking out to snatch his wife’s jewels from her locked box. Orlacs Hände is less concerned with autoeroticism than with the intimacy of human contact, connections between sex and violence and fears of class pollution. As Yvonne waits for Paul’s return from Nice, she lingers over a note from him – ‘I will embrace you … my hands will glide over you … and I will feel your body beneath my hands’ (ellipses in original) – which perhaps lends a slightly different urgency to her demand that Serral perform surgical miracles. After surgery, she tells Paul that she loves his hair and his tender hands, but her heavy-lidded gaze seems to be directed as much at his crotch. Whenever Yvonne reaches out to comfort him, he cannot bring himself to touch her with the hands of a killer. However, Nera commands Regine to ‘seduce’ Paul’s hands, and in a peculiar scene, she crawls up to her nervously distracted employer and kisses his hand; he withdraws it, but then reaches down to caress and hold her head, as if her class difference renders such contact less offensive to him. She responds, though, by crying out, ‘Don’t touch me … your hands hurt … like the hands of a killer’ (ellipses in original). Devastated by how much Vasseur’s hands must be polluting him if even the maid can sense it, and already convinced that their influence is seeping into him – ‘along the arms … until it reaches the soul … cold, terrible, relentless’ (ellipses in original) – Paul demands, without success, that Serral amputate them.

In Mad Love, these sexual undercurrents become more explicitly Freudian. Produced by MGM, it is rather less well-known than the Universal cycle of horror movies from the 1930s, and like MGM’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941), it does suffer from a certain stuffiness as its potentially tawdry material collides with a glamorous house style which – along with Gregg Toland and Chester Lyons’s luminous cinematography – makes it the most sumptuous of the three adaptations (the expressionist design of Doctor Gogol’s house and the sequence in which his mirror versions compel him to treachery are also visually  impressive). The studio’s middlebrow norms are apparent in the reworking of the narrative into an admittedly rather peculiar drawing-room love-triangle, in which Colin Clive’s Stephen is all quivering stiff-upper lip chipperness in the face of the disaster that has befallen him. Even in his more demented scenes, he is closer to the tormented Captain Stanhope Clive played in James Whale’s Journey’s End (1930) than the shrill hysteric Whale unleashed in Frankenstein (1931). But his role is less central than was Veidt’s, since the film was designed as a vehicle for recent Austro-Hungarian émigré Peter Lorre. Already known in the US for his performance as Hans Beckert, the serial child-killer in Fritz Lang’s M (1931), this was his first Hollywood film, and his presence required the transformation of the superhuman Cerral and the genial Serral into Doctor Gogol, whose sexual obsession with Yvonne Orlac drives the narrative. Lorre’s performance, switching effortlessly from compassionate and authoritative doctor to infant desiring approval, from passivity to anger, from melancholy to cackling madness, is every bit as potent as Veidt’s, and his disguise as Vasseur surpasses anything the other adaptations can offer.

impressive). The studio’s middlebrow norms are apparent in the reworking of the narrative into an admittedly rather peculiar drawing-room love-triangle, in which Colin Clive’s Stephen is all quivering stiff-upper lip chipperness in the face of the disaster that has befallen him. Even in his more demented scenes, he is closer to the tormented Captain Stanhope Clive played in James Whale’s Journey’s End (1930) than the shrill hysteric Whale unleashed in Frankenstein (1931). But his role is less central than was Veidt’s, since the film was designed as a vehicle for recent Austro-Hungarian émigré Peter Lorre. Already known in the US for his performance as Hans Beckert, the serial child-killer in Fritz Lang’s M (1931), this was his first Hollywood film, and his presence required the transformation of the superhuman Cerral and the genial Serral into Doctor Gogol, whose sexual obsession with Yvonne Orlac drives the narrative. Lorre’s performance, switching effortlessly from compassionate and authoritative doctor to infant desiring approval, from passivity to anger, from melancholy to cackling madness, is every bit as potent as Veidt’s, and his disguise as Vasseur surpasses anything the other adaptations can offer.

The film opens at Le Théatre des Horreurs, where Yvonne is starring in a one-act Grand Guignol, which Gogol – who ‘cures deformed children and mutilated soldiers’ – has attended every night of its run. His fixation is obvious when, contemplating the life-like waxwork of Yvonne in the lobby, he reprimands a drunken patron for speaking to it in an overly familiar manner, but its full extent only becomes clear as the play reaches its climax. Bound and stretched backwards over a torture wheel by a husband who suspects her of infidelity, Yvonne’s character refuses to name her lover, but as a red hot fork is applied to her flesh – somewhere below the bottom edge of the mid-shot – and the smoke of burning flesh rises before her, she screams, ‘Yes! Yes! It was your brother!’ Her ecstatic performance is clearly intended to be sexual, and should we be in any doubt, it is framed by two shots of Gogol, watching from between his box’s partially drawn curtains, his face half in shadow: ‘The first shot tracks in on his … face as the torture begins, his one clearly visible eye focused with startling intensity on the woman stretched on the torturer’s frame. The second shot, at the performance’s end, shows us that same eye closing in a kind of orgasmic satisfaction as her screams of pain reverberate around the theatre’ (Tudor 189).

The film opens at Le Théatre des Horreurs, where Yvonne is starring in a one-act Grand Guignol, which Gogol – who ‘cures deformed children and mutilated soldiers’ – has attended every night of its run. His fixation is obvious when, contemplating the life-like waxwork of Yvonne in the lobby, he reprimands a drunken patron for speaking to it in an overly familiar manner, but its full extent only becomes clear as the play reaches its climax. Bound and stretched backwards over a torture wheel by a husband who suspects her of infidelity, Yvonne’s character refuses to name her lover, but as a red hot fork is applied to her flesh – somewhere below the bottom edge of the mid-shot – and the smoke of burning flesh rises before her, she screams, ‘Yes! Yes! It was your brother!’ Her ecstatic performance is clearly intended to be sexual, and should we be in any doubt, it is framed by two shots of Gogol, watching from between his box’s partially drawn curtains, his face half in shadow: ‘The first shot tracks in on his … face as the torture begins, his one clearly visible eye focused with startling intensity on the woman stretched on the torturer’s frame. The second shot, at the performance’s end, shows us that same eye closing in a kind of orgasmic satisfaction as her screams of pain reverberate around the theatre’ (Tudor 189).

Backstage, Gogol discovers that Yvonne is not only married but is quitting the theatre for good to be with her husband, beginning with their postponed English honeymoon. She evades the agitated doctor, who later seizes an opportunity to try to overwhelm her with his passion. On leaving the theatre, he buys the waxwork, proposing to be Pygmalion to its Galatea. Meanwhile, Stephen’s train stops to pick up Rollo, an American circus knife-thrower convicted of murder. Rosset, the chief of police, invites an American journalist, Reagan, to witness Rollo’s arrival and execution, so that it can all be played down for the American press. The presence of Ted Healy’s Reagan, the kind of fast-talking character played so brilliantly by Roscoe Karns in the 1930s, and May Beatty’s turn as Gogol’s drunken housekeeper, Françoise, along with roles for such character actors as William Brophy, Billy Gilbert, Sara Haden, Henry Kolker and Ian Wolfe, suggest the extent to which Mad Love attempts to emulate the model provided by James Whale’s horror films, which were packed with eccentric types. However, unlike Whale, Freund is unable successfully to weave their idiosyncracies into a more general delirium. Brophy’s Rollo is undoubtedly the most endearing murderer the Production Code Administration (PCA) ever allowed, and the tone of the comedy is mild, except for the business between Reagan and Françoise, which is simultaneously the most Whale-like in its excesses and the least effective.

Rosset, Reagan and Yvonne travel together to the scene of the crash, which despite being elaborately mounted lacks Wiene’s sense of apocalyptic disorientation. While Wiene’s editing of the sequence produced a sense of instability, Freund’s scene is subject to Hollywood’s standardised continuity editing – spatial relations are clearly established, and Yvonne’s discovery of Stephen in the wreckage is brisk, to say the least. Rollo also survives the crash, only to be guillotined. When Yvonne begs Gogol to save rather than amputate Stephen’s hand, he arranges with Rosset to obtain the corpse and secretly performs the transplant. This time it is Yvonne who has a troubling dream – a keyboard Stephen is playing becomes a railway track, along which a train rushes, its spinning wheel becoming Gogol’s face. The doctor himself retires to his study, where he plays an organ while watching Yvonne’s mannequin in a mirror, wishing it would come to life. He leafs through Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portugese (1850), reading passages aloud.

Six months later, it is time to unbandage Orlac’s hands, which Gogol massages and probes in a shot which Reynold Humphrey’s suggests is more than merely an image of masturbation but of ‘the son lovingly masturbating his father’ (92). Certainly, the scene in the theatre can be interpreted as a primal scene fantasy, in which Gogol simultaneously ‘identifies with the position of the victim as a mother figure’ and ‘with the sadistic husband deriving intense pleasure from having his unfaithful wife branded’ and is positioned so that he can ‘occupy the absent place of the wife’s lover’ – the husband’s presumably younger brother (92). Arrested in his Oedipal trajectory – Gogol later asks Yvonne is she cannot even find ‘pity for a man who has never know the love of a woman’ – he frequently becomes childlike in her presence, casting her as the mother he desires and Stephen as the father whom he must do away with in order to become her lover. In the masturbation scene, then, Orlac struggles with his libidinal desires while trying to identify with and placate the father he is challenging.

Mad Love restores the novel’s reasons for the Stephen’s split with Edouard (who is renamed Henry and transformed from a notary into a jeweller and also, suggestively but without explanation, from a father into a step-father): Stephen’s decision to become a pianist – and marry Yvonne – rather than take over the family business. The sign above the shop, which reads ‘Orlac et fils Joailliers’, indicates the extent of Henry’s petit-bourgeois bitterness at Stephen for simultaneously rising above his station and marrying below it. He taunts Stephen – ‘being a tradesman wasn’t good enough for you … that actress you married … could supplement her earnings, eh?’ – who, enraged, throws a knife at his father, and races off to see Gogol, despairing that his hands ‘have a life of their own. They feel for knives. They want to throw them, and they know how to. … They want to kill’. The film’s self-consciousness about psychoanalysis becomes apparent when Gogol explains away Stephen’s behaviour: his ‘disturbed mind’ made susceptible by the twin shock of the accident and of his altered hands have brought into play an ‘arrested wish fulfilment’. He conjures up a hypothetical image of childhood playmates, one of whom threw a knife so ‘cleverly’ that Stephen’s inability to emulate it has ‘festered deep’ in his ‘subconscious’, and suggests that if Stephen could ‘bring that forgotten memory, whatever it is, into consciousness’ he ‘would be cured instantly’. The scene Gogol evokes is like a dream image of boys comparing their penises, although it is not clear that Gogol recognises this latent content. In the next scene, he tells Doctor Wong that he told Stephen ‘a lot of nonsense’ he himself does not believe, adding ‘I didn’t dare to tell him his hands are those of a murderer. That would probably drive him [pause] to commit murder himself’. This is the moment at which Gogol concocts his plot to steal Yvonne away from Stephen, but without realising that, given the role that knives will play in his scheme, he has become the infant envious of another’s phallic mastery.

Gogol kills Henry and, disguised, persuades Stephen that he is Rollo, whom Gogol has returned to life, sewing on his head and providing him with prosthetic hands. Stephen is arrested. Yvonne pushes her way into Gogol’s house and discovers the mannequin, which Gogol has dressed in a negligee (the PCA were particularly anxious about Gogol’s ownership of the mannequin, with Joseph Breen writing to warn against ‘any “suggestions of perversion” between Gogol and the wax figure’ (Humphreys 93)). Gogol returns home, dementedly gleeful over the success of his scheme. Yvonne poses as the mannequin, but a cut on her cheek gives her away. Gogol thinks his Galatea has come to life, but the image of the perfect woman – his mother – suddenly active and sexually accessible, complete with bleeding wound, is too much for him. Reciting Robert Browning’s ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ (1836), Gogol coils Yvonne’s hair around her neck so as to strangle her. In doing so, he takes on the role of the Grand Guignol’s cuckolded husband, with Yvonne gasping in sexualised agony beneath his hands. Stephen, brought there by the police, takes on both Gogol’s role of spectator as, through a grille, he witnesses his wife’s attempted murder, and that of the absent lover Gogol could not play. While Gogol merely collapsed in orgasmic bliss, Stephen throws the knife that kills Gogol, defeating his Oedipal challenge. Although Stephen’s hands kill, this life-taking is sanctioned by the law, and the heterosexual couple are reunited.

The Hands of Orlac is the last and by any reasonable measure the least of the adaptations. Presumably intended in some way to cash in on the succèss de scandale of such films as Et Dieu…créa la femme (Vadim 1956) and Les Amants (Malle 1958) and the related perception of French cinema as possessing greater sexual frankness, it certainly features the most passionate embraces of the adaptations. Moreover, it is repeatedly made clear that Stephen (Mel Ferrer) and Louise (as Yvonne is renamed) are sexually active while only being engaged. Indeed, Louise’s uncle does not think twice about lending the unchaperoned couple his villa. The film also features a low-rent cabaret act, in which the Eurasian Li-Lang, performs a burlesque routine involving a spangly bikini and a long feather boa; and she is instructed to seduce Stephen. While a vague eroticism hovers over Stephen and Louise’s more intimate moments, especially when his attempt to strangle her during lovemaking fleetingly evokes asphyxiophilia, the film’s overtness robs it of the psychosexual potential that the other variants exploit so well. In its place, we are left with a thriller that is more incoherent than thrilling and wastes its most interesting potential innovation.

After his plane crash, the ambulance rushing Stephen to hospital is stopped by the police since the road is closed for the transportation of Vasseur to his place of execution. Louise pleads with the police to let them through, since Vasseur’s hands ‘will never strangle again but the hands of Orlac can still be saved’. Stephen, barely conscious overhears this exchange. Later, in a delirium, he sees the (animated) headlines on side-by-side newspaper stories become jumbled and transposed. The panned-and-scanned television format crops the ends of the headlines, but the sequence goes (roughly) like this: LOUIS VASSEUR PAIE SES CRIMES and STEPHEN ORLAC PERO SES MAINS, which become LOUIS VASSEUR LOSES HIS HEAD and STEPHEN ORLAC LOSES HIS HANDS, then LOUIS VASSEUR WILL STRANGLE NO MORE and STEPHEN ORLAC WILL HE PLAY AGAIN? and then LOUIS VASSEUR WILL HE PLAY NO MORE and STEPHEN ORLAC WILL STRANGLE AGAIN and then THE STRANGLER GETS THE KNIFE and THE STRANGLER STEPHEN ORLAC GETS NEW HANDS. Finally, the second headline fills the screen, becoming STEPHEN ORLAC GETS THE HANDS OF and then LOUIS VASSEUR THE STRANGLER. One of the least satisfactory aspects of the novel and first adaptation is the sudden revelation of Vasseur’s innocence. This jars because it resolves the tension between the two possible explanations – either Orlac is possessed by the transplanted hands of a killer or he is going mad – by abruptly introducing a third for which no adequate groundwork has been laid and which upsets any moral order concerning just rewards. Surely Orlac should be even more troubled that his hands are those of an innocent man wrongfully executed? Mad Love avoids this problem inasmuch as Rollo was actually a killer, but that instead leaves a shadow over Orlac’s future – he has the hands and skills of a killer! – which the film forestalls by ending as swiftly as possible. The Hands of Orlac’s headline sequence suggests that the film might overcome such clumsy conclusions by ultimately revealing that there has been no surgery, and that Stephen’s fears and actions are the product solely of his traumatised imagination. This possibility lingers for a while, lending effectiveness to the sequence of scenes that begin with Louise protesting that he will bruise her arms if he holds them so tightly when they kiss. Orlac then tries out a fairground strength machine, which shows his grip to be unnaturally strong. Returning home with his prize, he listens to a recording of an earlier concert but cannot play along with it on the piano. In quick succession, he discovers that a ring no longer fits, that his gloves are bursting at the seams and that his handwriting has changed. Distraught, he tries to telephone the surgeon, Volcheff, and the assistant who takes the call refers to Orlac’s ‘new hands’. His fingers, resting on a table edge, seem to take on a life of their own, playing along to the recording. Distracted and distressed, he unintentionally pulls the head off the doll he won at the fair. Sadly, however, the film soon loses interest in following this potentially intriguing revision (ultimately La Sûreté reveal to Scotland Yard that the real killer has confessed and Vasseur was innocent), and instead clumsily reworks the Nera/Gogol blackmail plot.

Although a pet cat shies away from his hands at Louise’s uncle’s villa (in the French version, Stephen, strangely troubled by a picture of a guillotine execution, wakes in the night and goes on to the balcony, where the cat again flees him), Stephen seems to be recovering, until the cat is found with its neck broken. The maid is quick to blame it on gypsies, but the gardener suspects Stephen, who, furious, attacks the old man. After nearly strangling Louise in a moment of passion, Stephen takes up pseudonymous residence in a seedy backstreet hotel in Marseilles (on the streets of which he encounters a prostitute, who recoils from the touch of his hands). Neron (Christopher Lee), a fellow guest and nightclub magician, calculates that this newcomer must be rich, and orders his assistant, Li-Lang, to seduce him, intending to burst in on them in a compromising position. She is less than willing – ‘You made me a slut’, she protests; ‘Made?’ Neron replies, ‘My dear, I couldn’t stop you. You were born a slut and will always be one. It is I who have lowered myself’ – but Neron compels her. (He is several times shown with a collection of marionettes, one of which, a skeleton used in his stageshow, alludes to a figure in de Crochans’ apartment, but despite giving insight into Neron’s perception of himself as a consummate puppet-master they lack the critical Expressionist effect of Veidt’s puppet-like movements.) However, before the honey-trap can be played out, Louise traces Stephen to the hotel. Overhearing Stephen explaining his fear that his hands are those of a killer, Neron drastically revises his scheme – to one which makes no discernible sense.

Although a pet cat shies away from his hands at Louise’s uncle’s villa (in the French version, Stephen, strangely troubled by a picture of a guillotine execution, wakes in the night and goes on to the balcony, where the cat again flees him), Stephen seems to be recovering, until the cat is found with its neck broken. The maid is quick to blame it on gypsies, but the gardener suspects Stephen, who, furious, attacks the old man. After nearly strangling Louise in a moment of passion, Stephen takes up pseudonymous residence in a seedy backstreet hotel in Marseilles (on the streets of which he encounters a prostitute, who recoils from the touch of his hands). Neron (Christopher Lee), a fellow guest and nightclub magician, calculates that this newcomer must be rich, and orders his assistant, Li-Lang, to seduce him, intending to burst in on them in a compromising position. She is less than willing – ‘You made me a slut’, she protests; ‘Made?’ Neron replies, ‘My dear, I couldn’t stop you. You were born a slut and will always be one. It is I who have lowered myself’ – but Neron compels her. (He is several times shown with a collection of marionettes, one of which, a skeleton used in his stageshow, alludes to a figure in de Crochans’ apartment, but despite giving insight into Neron’s perception of himself as a consummate puppet-master they lack the critical Expressionist effect of Veidt’s puppet-like movements.) However, before the honey-trap can be played out, Louise traces Stephen to the hotel. Overhearing Stephen explaining his fear that his hands are those of a killer, Neron drastically revises his scheme – to one which makes no discernible sense.

Stephen and Louise reconcile (the French version extends this sequence) and marry. However, just before his first performance in a new tour, he receives a package containing a pair of gloves, with Vasseur’s name stamped inside. As he plays, he sees his hands transform into those of the gloved killer, causing him to flee the stage mid-concert. The following day, a sculptor, Graham Coates, asks if he can use Orlac’s hands as the model for those of Lazarus, stretching out from the tomb (in the French version, he also tries to hand a ball back to a young girl playing in the park, but she too is terrified of his hands). Soon after, Li-Lang, disguised as Vasseur’s widow, visits Louise and tells her that the spirit of her husband cannot rest until Stephen returns something that belongs to him. Suspecting that Volchett did indeed perform a hand transplant, Louise flies to Paris to question him, only to discover that he has just collapsed from a cerebral haemorrhage (in the novel Cerral died at sea just when his testimony was most needed). An increasingly paranoid Stephen discovers that Louise and her uncle have lied about her whereabouts. In the middle of the night, Stephen wakes to find the hook-handed and corpse-like Vasseur looming over him – but then, promptly and quite mystifyingly, Neron removes the disguise and warns Stephen that Louise and her uncle intend to have him committed. (It is impossible to work out how Neron intends to make money from this, but presumably it has something to do with the sample of Stephen’s handwriting that Li-Lang – for reasons that are never explained – stole from the Orlacs’ apartment.) Louise, her suspicions aroused, tracks down Li-Lang. Neron overhears his assistant telling her to bring the police to the club that night. Later, Stephen overhears a conversation between Louise and her uncle which seems to confirm their plan to commit him. That night, Neron murders Li-Lang during the course of their act. Stephen attacks him, delaying his escape until the police arrive. It is revealed that Vasseur was not a killer, leaving Stephen free to return to his wife and career.

Unfortunately, the incoherence of The Hands of Orlac – which seems as much a consequence of its screenplay and conditions of production as of its subsequent editings-down – never achieves the dreamlike or hysterical qualities of either the novel or the earlier adaptations. The most severely amputated of the variants, it fails to take on a life of its own.

Notes

Notes

[1] Since I wrote this, Brian Stableford has translated five volumes of Renard for Black Coat Press.

References

Lotte H. Eisner, The Haunted Screen, trans. Roger Greaves. London: Martin Secker and Warburg, 1973.

Arthur B. Evans, ‘The Fantastic Science Fiction of Maurice Renard’, Science-Fiction Studies 64 (1994): 380–396.

Reynold Humphries, The Hollywood Horror Film, 1931–1941: Madness in a Social Landscape. New York: The Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Friedrich A. Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Maurice Renard, The Hands of Orlac, trans. Iain White. London: Souvenir Press, 1981.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

David J. Skal, The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror. New York: W.W. Norton, 1993.

Andrew Tudor, Monsters and Mad Scientists: A Cultural History of the Horror Movie. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989.

and so anyway it turns out that the best thing about Paul Wegener’s Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (1920) is not the stunning 4K restoration, which makes it look like a completely different film to the one that’s only been available in shitty prints and ropey transfers for decades, nor is it sniggering at the subtitle, which I am told by a German friend would nowadays mean ‘and how he ejaculated into the world’ , no, the very best thing about this film about a creature fashioned from clay and brought to life through mystical powers, is the way it it loses all credibility the moment Fabian (Lothar Muthel, below right, shirt-cocking, full-Winnie-the-Pooh) starts to express an interst in, well, girls…

and so anyway it turns out that the best thing about Paul Wegener’s Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (1920) is not the stunning 4K restoration, which makes it look like a completely different film to the one that’s only been available in shitty prints and ropey transfers for decades, nor is it sniggering at the subtitle, which I am told by a German friend would nowadays mean ‘and how he ejaculated into the world’ , no, the very best thing about this film about a creature fashioned from clay and brought to life through mystical powers, is the way it it loses all credibility the moment Fabian (Lothar Muthel, below right, shirt-cocking, full-Winnie-the-Pooh) starts to express an interst in, well, girls…

and so anyway it turns out that the best thing about Sir Diddley Squat’s latest xenomorph instalment is that after the prologue – and if you overlook the clunky dialogue, indistinguishability of the ‘characters’, poor grasp of physics, idiot plotting and general boring-ness of it all – most of the first hour is nowhere near as bad as Prometheus (Scott 2012) or, indeed, as the second half of Alien: Covenant, even if the second half is the half in which we get to see Michael Fassbender in a dopey hat, Michael Fassbender play Kurtz as Hannibal Lecter, Michael “you blow into it and I’ll do the fingering” Fassbender finally have a queer romance with Michael Fassbender, and, in the very final shot, Michael Fassbender show off his enormous feet in clown shoes…

and so anyway it turns out that the best thing about Sir Diddley Squat’s latest xenomorph instalment is that after the prologue – and if you overlook the clunky dialogue, indistinguishability of the ‘characters’, poor grasp of physics, idiot plotting and general boring-ness of it all – most of the first hour is nowhere near as bad as Prometheus (Scott 2012) or, indeed, as the second half of Alien: Covenant, even if the second half is the half in which we get to see Michael Fassbender in a dopey hat, Michael Fassbender play Kurtz as Hannibal Lecter, Michael “you blow into it and I’ll do the fingering” Fassbender finally have a queer romance with Michael Fassbender, and, in the very final shot, Michael Fassbender show off his enormous feet in clown shoes… and so anyway it turns out the best thing about Overlord (2018) is, as any sane person would expect, the always awesome Bokeem Woodbine, though the second best thing about this very silly film featuring a mission behind German lines in Normandy in the early hours of 6 June 1944 discovering mad scientists manufacturing a Nazi zombie army is the way it poses a mystery every bit as big as how Bokeem “Okay I’ll Be In It, And The Best Thing In It, But Only For 5 minutes” Woodbine makes a living, namely, how in the hell was this film not called D-Day of the Dead

and so anyway it turns out the best thing about Overlord (2018) is, as any sane person would expect, the always awesome Bokeem Woodbine, though the second best thing about this very silly film featuring a mission behind German lines in Normandy in the early hours of 6 June 1944 discovering mad scientists manufacturing a Nazi zombie army is the way it poses a mystery every bit as big as how Bokeem “Okay I’ll Be In It, And The Best Thing In It, But Only For 5 minutes” Woodbine makes a living, namely, how in the hell was this film not called D-Day of the Dead

Just back from finally seeing Mother! at a late screening. For me, it reiterates with startling clarity Aronofksy’s three key themes, all of which are evident throughout, but each of which in turn comes to the fore in the film’s three sections.

Just back from finally seeing Mother! at a late screening. For me, it reiterates with startling clarity Aronofksy’s three key themes, all of which are evident throughout, but each of which in turn comes to the fore in the film’s three sections. Once upon a time, in contemporary Denmark, there were two middle-aged, infertile half-brothers, each of whom lost his mother in childbirth.

Once upon a time, in contemporary Denmark, there were two middle-aged, infertile half-brothers, each of whom lost his mother in childbirth. [The last of the pieces written for that book on sf adaptations that never appeared]

[The last of the pieces written for that book on sf adaptations that never appeared]

wonder’ psychiatrist, Dr Katherine McMichaels (Barbara Crampton), to determine whether Tillinghast can stand trial. Along with the cop Buford ‘Bubba’ Brownlee (Ken Foree), she takes him back to the house, where she discovers evidence of Pretorius’s BDSM predilections and reconstructs the experiment that, according to Tillinghast, released whatever killed his mentor. A toothed, tentacled creature attacks Bubba, and Pretorius returns, monstrously transformed, before Tillinghast can switch off the machine. McMichaels, sexually aroused by the Resonator’s stimulation of her pineal gland, is compelled to turn it back on. Pretorius returns in even more hideous form. The enormous slug-like creature that sucked his head from his shoulders fastens on to Tillinghast, tearing of his hair before the Resonator is again switched off. McMichaels, fascinated by the BDSM clothes and equipment in Pretorius’s room, dresses up in dominatrix gear and attempts to have sex with the unconscious Tillinghast and with Bubba. Her sexual energy reactivates the Resonator, unleashing locusts that strip Bubba’s flesh to the bone. Returned to the asylum, the mutating Tillinghast becomes hungry for human brains. He sucks out one of Bloch’s eyes and eats her brain through the socket. McMichaels and Tillinghast return to Pretorius’s house for another extravagant display of sexual apparatuses and gloopy special effects before the Resonator is destroyed.

wonder’ psychiatrist, Dr Katherine McMichaels (Barbara Crampton), to determine whether Tillinghast can stand trial. Along with the cop Buford ‘Bubba’ Brownlee (Ken Foree), she takes him back to the house, where she discovers evidence of Pretorius’s BDSM predilections and reconstructs the experiment that, according to Tillinghast, released whatever killed his mentor. A toothed, tentacled creature attacks Bubba, and Pretorius returns, monstrously transformed, before Tillinghast can switch off the machine. McMichaels, sexually aroused by the Resonator’s stimulation of her pineal gland, is compelled to turn it back on. Pretorius returns in even more hideous form. The enormous slug-like creature that sucked his head from his shoulders fastens on to Tillinghast, tearing of his hair before the Resonator is again switched off. McMichaels, fascinated by the BDSM clothes and equipment in Pretorius’s room, dresses up in dominatrix gear and attempts to have sex with the unconscious Tillinghast and with Bubba. Her sexual energy reactivates the Resonator, unleashing locusts that strip Bubba’s flesh to the bone. Returned to the asylum, the mutating Tillinghast becomes hungry for human brains. He sucks out one of Bloch’s eyes and eats her brain through the socket. McMichaels and Tillinghast return to Pretorius’s house for another extravagant display of sexual apparatuses and gloopy special effects before the Resonator is destroyed.

him uncontrollably violent. The medical staff set out to find him. Shortly after the tipping-point passes, Angela is found murdered, her skull crushed and her body repeatedly stabbed post-mortem.

him uncontrollably violent. The medical staff set out to find him. Shortly after the tipping-point passes, Angela is found murdered, her skull crushed and her body repeatedly stabbed post-mortem.

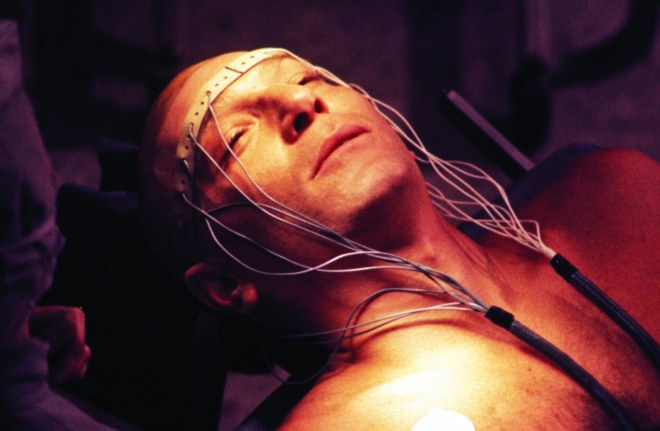

When Benson arrives at the hospital, Morris signs for him ‘as if he were receiving a package from United Parcel’ (8), a subjection to bureaucratic processes that resonates with the patient’s psychosis. McPherson later suggests that Benson has been turned into ‘a read-out device’ for the implanted computer, ‘as helpless to control the read-out as a TV screen is helpless to control the information presented on it’ (83; italics in original). The hospital computer refers to Benson as an ‘auxillary unit’ (120), while he describes himself as ‘an automobile in a complicated service station’ (125). Morris begrudges his pager, which keeps him perpetually networked into administrative systems, and at one point suddenly notices that computers monitor and predict LA traffic flows. Such ruminations are given a sense of inevitable – and detrimental – consequence through the linear determinism espoused by several characters and by the frequency with which futurological and computer projections are treated as inarguable: in 1967, McPherson surveyed the fields of ‘diagnostic conceptualization, surgical technology, and microelectronics’ and concluded that it would be possible to perform ‘an operation for ADL seizures in July of 1971’ (197), a prediction which proved too conservative by four months; and the positive progression cycle, in which Benson’s brain learns to trigger seizures, is plotted from just three points on a graph, predicting to within a couple of minutes when he will go into continuous stimulation. Consequently, when Morris is told about July 1969’s ‘Watershed Week’ – ‘when the information-handling capacity of all the computers in the world exceeded the information-handling capacity of all the human brains in the world’ – and that by 1975 computers will ‘lead human beings by fifty to one in terms of capacity’ (159-60), the novel succeeds in conveying a sense of menace. This is achieved by conflating a not unreasonable prediction of quantitative change with the implication that it must necessarily result in a threat to humanity – or at least to our human qualities (which consist entirely of small-town, middle-American values).

When Benson arrives at the hospital, Morris signs for him ‘as if he were receiving a package from United Parcel’ (8), a subjection to bureaucratic processes that resonates with the patient’s psychosis. McPherson later suggests that Benson has been turned into ‘a read-out device’ for the implanted computer, ‘as helpless to control the read-out as a TV screen is helpless to control the information presented on it’ (83; italics in original). The hospital computer refers to Benson as an ‘auxillary unit’ (120), while he describes himself as ‘an automobile in a complicated service station’ (125). Morris begrudges his pager, which keeps him perpetually networked into administrative systems, and at one point suddenly notices that computers monitor and predict LA traffic flows. Such ruminations are given a sense of inevitable – and detrimental – consequence through the linear determinism espoused by several characters and by the frequency with which futurological and computer projections are treated as inarguable: in 1967, McPherson surveyed the fields of ‘diagnostic conceptualization, surgical technology, and microelectronics’ and concluded that it would be possible to perform ‘an operation for ADL seizures in July of 1971’ (197), a prediction which proved too conservative by four months; and the positive progression cycle, in which Benson’s brain learns to trigger seizures, is plotted from just three points on a graph, predicting to within a couple of minutes when he will go into continuous stimulation. Consequently, when Morris is told about July 1969’s ‘Watershed Week’ – ‘when the information-handling capacity of all the computers in the world exceeded the information-handling capacity of all the human brains in the world’ – and that by 1975 computers will ‘lead human beings by fifty to one in terms of capacity’ (159-60), the novel succeeds in conveying a sense of menace. This is achieved by conflating a not unreasonable prediction of quantitative change with the implication that it must necessarily result in a threat to humanity – or at least to our human qualities (which consist entirely of small-town, middle-American values). Curiously, though, Crichton also struggles at times to express a sense of the complex, non-linear determinism underpinning his trademark narrative about the failure of complex systems, best – if still rather clumsily – articulated through the chaos mathematics he invokes in Jurassic Park (1990). In The Terminal Man, it is most clearly developed through Gerhard’s computer programmes, called Saint George and Martha. Designed to interact with each other, they are capable of responding ‘with three emotional states – love, fear, and anger’ and of ‘produc[ing] three actions – approach, withdrawal, attack’ (99). Despite this system’s simplicity, it ‘produce[s] complex and unpredictable machine behavior’ (115). After running more than a hundred times, Saint George, ‘programmed for saintliness’, ‘is learning not be a saint around Martha’ (103), even threatening to kill her. This is presented as a value-neutral experiment, but the obvious gender stereotyping suggests that the dependence on initial conditions need not be that sensitive to produce this result. The implications of a later discussion, in which Gerhard and Ross contemplate the possibility that after twenty-four hours of stimulations Benson’s brain has become something radically different than the one on which they operated and thus beyond their capacity to predict, are likewise countered by the utter predictability of the plot.

Curiously, though, Crichton also struggles at times to express a sense of the complex, non-linear determinism underpinning his trademark narrative about the failure of complex systems, best – if still rather clumsily – articulated through the chaos mathematics he invokes in Jurassic Park (1990). In The Terminal Man, it is most clearly developed through Gerhard’s computer programmes, called Saint George and Martha. Designed to interact with each other, they are capable of responding ‘with three emotional states – love, fear, and anger’ and of ‘produc[ing] three actions – approach, withdrawal, attack’ (99). Despite this system’s simplicity, it ‘produce[s] complex and unpredictable machine behavior’ (115). After running more than a hundred times, Saint George, ‘programmed for saintliness’, ‘is learning not be a saint around Martha’ (103), even threatening to kill her. This is presented as a value-neutral experiment, but the obvious gender stereotyping suggests that the dependence on initial conditions need not be that sensitive to produce this result. The implications of a later discussion, in which Gerhard and Ross contemplate the possibility that after twenty-four hours of stimulations Benson’s brain has become something radically different than the one on which they operated and thus beyond their capacity to predict, are likewise countered by the utter predictability of the plot. The film opens in pitch black night, the only light emanating from the cockpit of an insectile police helicopter facing the camera, the only noise that of its engines as it takes to the air; the helicopter will become an aggressively loud presence, signalling the powerlessness not merely of Benson (George Segal) to avoid it but of the audience in the face of the system it represents. The film cuts to a restaurant, in which doctors Ellis (Richard Dysart), McPherson (Donald Moffat) and Friedman (James Sikking) discuss Benson and ADL syndrome. Benson’s back-story is related, with impressive economy, through a series of photographs that the three men examine – Benson with his wife and daughter, Benson being arrested, the battered face of Benson’s wife – while planning the media coverage of the operation. To Hodges’ regret, he added this sequence to help allay studio concerns that ‘the film had no one to root for’ (personal email) rather than cutting

The film opens in pitch black night, the only light emanating from the cockpit of an insectile police helicopter facing the camera, the only noise that of its engines as it takes to the air; the helicopter will become an aggressively loud presence, signalling the powerlessness not merely of Benson (George Segal) to avoid it but of the audience in the face of the system it represents. The film cuts to a restaurant, in which doctors Ellis (Richard Dysart), McPherson (Donald Moffat) and Friedman (James Sikking) discuss Benson and ADL syndrome. Benson’s back-story is related, with impressive economy, through a series of photographs that the three men examine – Benson with his wife and daughter, Benson being arrested, the battered face of Benson’s wife – while planning the media coverage of the operation. To Hodges’ regret, he added this sequence to help allay studio concerns that ‘the film had no one to root for’ (personal email) rather than cutting  directly to the title sequence: a black screen with white credits, accompanied by Glenn Gould’s performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variation No. 25; footsteps approach in a corridor; a key chain rattles; there is a scraping sound, a peephole opens on the right of the screen and an eye peers through, looking out at the audience; the men in the corridor, functionaries of some institution, discuss Benson; the caption ‘tuesday’ appears, and the film cuts to Benson being delivered by the police to the hospital. Three more times during the film the screen goes to black, a peephole opens, and these anonymous, uneducated men – it is not clear if they are prison warders or asylum orderlies – discuss Benson. The film also ends with a version of this shot, in which one of the voices says, ‘They want you next’, to which the other responds ‘Quit kidding around’. These final words comically deflate the clichéd threat intoned by the first speaker; but beneath the end credits, the police helicopter descends through the night, coming full circle, yet instead of the deafening rotors there is silence, and then a cold wind howls. This hesitation – erasing then reinstating the film’s ominous implications – indicate Hodges’ wry amusement at the materials with which he is working and, simultaneously, a genuine sense that, despite their pulpiness, they can be utilised to critique contemporary social realities.

directly to the title sequence: a black screen with white credits, accompanied by Glenn Gould’s performance of Bach’s Goldberg Variation No. 25; footsteps approach in a corridor; a key chain rattles; there is a scraping sound, a peephole opens on the right of the screen and an eye peers through, looking out at the audience; the men in the corridor, functionaries of some institution, discuss Benson; the caption ‘tuesday’ appears, and the film cuts to Benson being delivered by the police to the hospital. Three more times during the film the screen goes to black, a peephole opens, and these anonymous, uneducated men – it is not clear if they are prison warders or asylum orderlies – discuss Benson. The film also ends with a version of this shot, in which one of the voices says, ‘They want you next’, to which the other responds ‘Quit kidding around’. These final words comically deflate the clichéd threat intoned by the first speaker; but beneath the end credits, the police helicopter descends through the night, coming full circle, yet instead of the deafening rotors there is silence, and then a cold wind howls. This hesitation – erasing then reinstating the film’s ominous implications – indicate Hodges’ wry amusement at the materials with which he is working and, simultaneously, a genuine sense that, despite their pulpiness, they can be utilised to critique contemporary social realities. surgeons. While Crichton does acknowledge the sexism Ross faces, including incidents and passages of introspection, Hodges’ low-key spatialisation of patriarchal hegemony is far more effective. This spatialisation of gendered power is further emphasised during the sequence in which Ross’s discomfiture, when alone with Benson during the testing of his electrodes, is ignored by the male doctors observing them through one-way glass positioned high on the wall above them. The Foucauldian aspects of commonplace surveillance are even more clearly evinced during the lengthy surgical procedurals – articulated through an impeccable low-key precision, self-consciously devoid of the melodramatic imperatives shaping such sequences in Crichton’s E.R. (1994–2009) – as a crowd gathers around to observe the operation from above.

surgeons. While Crichton does acknowledge the sexism Ross faces, including incidents and passages of introspection, Hodges’ low-key spatialisation of patriarchal hegemony is far more effective. This spatialisation of gendered power is further emphasised during the sequence in which Ross’s discomfiture, when alone with Benson during the testing of his electrodes, is ignored by the male doctors observing them through one-way glass positioned high on the wall above them. The Foucauldian aspects of commonplace surveillance are even more clearly evinced during the lengthy surgical procedurals – articulated through an impeccable low-key precision, self-consciously devoid of the melodramatic imperatives shaping such sequences in Crichton’s E.R. (1994–2009) – as a crowd gathers around to observe the operation from above. flirt with Angela (Jill Clayburgh)) seem to bemuse the other characters. Retrospectively, George Segal seems an unlikely Benson. Despite a successful career as a dramatic actor on stage, television and film, by the early 1970s he was focusing on the kind of comedy roles with which he has subsequently become most closely associated. By effectively casting him against type, Hodges produces a soft-spoken, genial everyman who is overtaken by external forces (the pre-credits material is, indeed, a misstep, giving Benson too much specificity, and counteracting the effectiveness of a later scene in which a recording of his litany of suburban lifestyle elements and possessions plays on multiple diegetic screens). He is particularly effective when his actions – stabbing Angela, attacking the robot on which he had been working – become mechanical, taking control of his body.

flirt with Angela (Jill Clayburgh)) seem to bemuse the other characters. Retrospectively, George Segal seems an unlikely Benson. Despite a successful career as a dramatic actor on stage, television and film, by the early 1970s he was focusing on the kind of comedy roles with which he has subsequently become most closely associated. By effectively casting him against type, Hodges produces a soft-spoken, genial everyman who is overtaken by external forces (the pre-credits material is, indeed, a misstep, giving Benson too much specificity, and counteracting the effectiveness of a later scene in which a recording of his litany of suburban lifestyle elements and possessions plays on multiple diegetic screens). He is particularly effective when his actions – stabbing Angela, attacking the robot on which he had been working – become mechanical, taking control of his body. Finally, there is the revised ending of the story. Rather than seeing off Benson’s attack with her microwave, Ross, fearing he might attack her, holds out a knife towards him. In a moment of lucidity between stimulations, he walks onto the blade. Instead of launching an assault on the hospital computer, Benson then heads to a cemetery and descends into an open grave. The police close in and while Ross struggles to reach her patient, the police helicopter appears once more, bearing the sniper who will shoot Benson. People rush forward, and from the bottom of the grave we see them forced back by police whose vizored helmets recall not only those worn by the surgeons while they operated on Benson but also the brutally anonymous robot police of THX 1138 (Lucas 1971).

Finally, there is the revised ending of the story. Rather than seeing off Benson’s attack with her microwave, Ross, fearing he might attack her, holds out a knife towards him. In a moment of lucidity between stimulations, he walks onto the blade. Instead of launching an assault on the hospital computer, Benson then heads to a cemetery and descends into an open grave. The police close in and while Ross struggles to reach her patient, the police helicopter appears once more, bearing the sniper who will shoot Benson. People rush forward, and from the bottom of the grave we see them forced back by police whose vizored helmets recall not only those worn by the surgeons while they operated on Benson but also the brutally anonymous robot police of THX 1138 (Lucas 1971).

[This is one of several pieces written several years ago for a book on sf adaptations that never appeared]

[This is one of several pieces written several years ago for a book on sf adaptations that never appeared] Wilson, posing as a friend of his old self, visits his daughter but is disillusioned by her view of the man he had been. Despite the company’s efforts to dissuade him, Wilson also visits his own ‘widow’, but to his surprise and dismay Emily has moved on with her life, remodelling and redecorating the house, effectively removing all trace of him. He surrenders to the company, imagining that he is going to be reborn again, this time with his input so as to avoid the errors of the first attempt. Spending his days in a room full of mildly tranquillised men, including Charley, he is badgered for the names of friends or acquaintances who might be interested in the company’s service. When he is finally summoned for surgery, he slowly and resignedly realises that he is not going to be reborn. He is to contribute his corpse to another client’s fake death.

Wilson, posing as a friend of his old self, visits his daughter but is disillusioned by her view of the man he had been. Despite the company’s efforts to dissuade him, Wilson also visits his own ‘widow’, but to his surprise and dismay Emily has moved on with her life, remodelling and redecorating the house, effectively removing all trace of him. He surrenders to the company, imagining that he is going to be reborn again, this time with his input so as to avoid the errors of the first attempt. Spending his days in a room full of mildly tranquillised men, including Charley, he is badgered for the names of friends or acquaintances who might be interested in the company’s service. When he is finally summoned for surgery, he slowly and resignedly realises that he is not going to be reborn. He is to contribute his corpse to another client’s fake death.