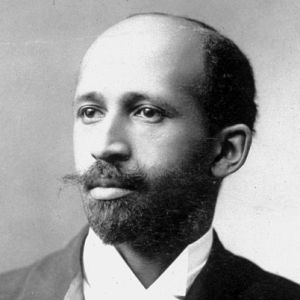

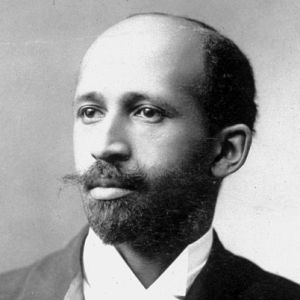

‘The Princess Steel’, a previously unpublished sf/fantasy story by W.E.B. Du Bois, can be found in the most recent issue of the PMLA (130.3: 819-829). It was written some time between 1908 and 1910, and there is an earlier draft called ‘The Megascope: A Tale of Tales’.

‘The Princess Steel’, a previously unpublished sf/fantasy story by W.E.B. Du Bois, can be found in the most recent issue of the PMLA (130.3: 819-829). It was written some time between 1908 and 1910, and there is an earlier draft called ‘The Megascope: A Tale of Tales’.

The earlier title acknowledges Du Bois’s self-conscious embedding of one tale within another within another. It also shows a clear sense of how the introduction of a science-fictional innovation (not really what Suvin means by the novum) functions as a narratological device to generate fictions. The Megascope shifts the story from one genre/diegesis into another and then into another – or, perhaps more accurately, revises the reader’s expectations of the story as it rewrites the rules of the world in which the story takes place.

‘The Princess Steel’ begins as an apparently realist story in contemporary New York, told with a certain wry humour, as the unnamed protagonist and his wife, in response to a newspaper advertisement, go to witness a scientific demonstration by the sociologist Professor Hannibal Johnson:

Now my wife and I were interested in Sociology; we had studied together at Chicago, so diligently indeed that we had just married and were spending our honeymoon in New York. … it certainly seemed very opportune to hear almost immediately upon our arrival of a great lecturer in Sociology albeit his name, to our chagrin, was new to us. (822)

To their even greater chagrin, Johnson is black (and initially they assume he must be the Professor’s servant). On reflection, however,

One would not for a moment have hesitated to call him a gentleman had it not been for his color. His voice, his manner, everything showed training and refinement. Naturally my wife stiffened and drew back and yet she felt me smiling and hated to acknowledge the failure of our expedition. (822)

This is an intriguing passage in that it is also the one at which we realise that the newly-weds are white. Their studies provide a clue to the likelihood of this, but it is only their assertion of the colour line that definitively places them on one side of it. By making it manifest in this way, Du Bois prepares the ground for a story that will use fantasy so as to imagine some of the determining forces of everyday life that many varieties of realism and naturalism, with their emphasis on surface detail, interpersonal relations and individual psychology, struggle to capture. Like naturalist Frank Norris’s incomplete trilogy of wheat (The Octopus (1901), The Pit (1903)), Du Bois’s first novel, The Quest of the Silver Fleece (1911), is an epic that attempts to map out the complex social relations of a single industry (for Du Bois, cotton); but even Norris, especially in his first novel, bows under the weight of the task and includes weirdly ecstatic visions, as if the real were too complex for mere realism. In this context, one cannot help but also recall the fantastical spirit that imbues Du Bois’s second novel, The Dark Princess (1928), especially when it draws closest to heavy industry in the stunning passage when protagonist Matthew Towns chucks it all in to become a manual labourer digging the subway tunnels:

Lakes and rivers flow … pouring from the hills down to the kitchen sinks with steady pulse beneath the iron street [and] great steel Genii, a hundred feet high, lumber blindly along at out neck and call to dig, lift, talk, push, weep, and swear [and us] houses sag, stagger, and reel … but …do not fall: we hold them, force them and prop them up [even as we] tak[e] away the foundations of the city and leav[e] it delicately swaying on air. (265, 266).

In ‘The Princess Steel’, however, Du Bois approaches the problem from the other side. His broadly realistic opening is just a frame for an exercise in the fantastic, using sf to access the allegorical as a means to draw out the unseen determinants of an exploitative patriarchal-colonial-capitalist modernity and contemporary social life.

Johnson’s library contains volume upon volume of The Great Chronicle – a record he discovered a quarter century earlier of the ‘everyday facts of life but kept with surprising accuracy by a Silent Brotherhood for 200 years’ (823). We learn no more about this surveillant order – perhaps for Du Bois an imaginative precursor to The Dark Princess’s secretive revolutionary Great Central Committee of Yellow, Brown and Black – but their copious records have enabled Johnson to develop the Megascope.

Rather than plunge into directly into allegory or deploy the kind of slippery kind transition into an alternative realm deployed in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) – I am insufficiently familiar with Du Bois’s biography to know whether he had read Mark Twain’s novel, but it does seem to me to lurk in the background of what is to come – Du Bois turns to scientific innovation, the very stuff of modernity, to investigate modernity. (Foucault scholars will be excited to learn that Du Bois begins with technologies of statistics and surveillance; Hegelians will have to wait a few moments longer for their fix.)

Professor Johnson first shows his visitors a mechanism by which a human deed can be represented in two dimensions on a ‘thin transparent film’ (823). Layering such films one on top of another produces a representation of the ‘history of these deeds in days and months and years’ (823) and, he explains, if

“these planes be curved about one center and reflected to and fro we get a curve of infinite curvings which is—”—he paused impressively—“which is the Law of Life.” (823)

He next reveals the ‘vast solid crystal globe’, ‘fifty feet in diameter’, on which he has spent twenty years plotting the curves of life; and for twenty years he has been thwarted in his quest for the ‘Great Curve … by curious counter-curves and shadow and crossing’ (823). This endless frustration has led him to hypothesise that

Human life is not alone on earth—there is an Over-life—nay—nay I mean nothing metaphysical or theological—I mean a social Over-life—a life of Over-men, Super men, not merely Captains of Industry but field marshalls of the Zeit-geist, who today are guiding the world events and dominating the lives of men. It is a Life so near ourselves that we think it is ourselves, and yet so vast that we vaguely identify it with the universe. (823)

And so he reveals the Megascope, with which he will reveal an Over-Man. First they see

the Curve of Steel—the sum of all the facts and quantities and times and lives that go to make Steel, that skeleton of the Modern World … the Spirit of the wonderful metal which is the center of our modern life, and the inner life of the Over-life that dominates this vast industry— (824)

I love this slightly awkward description of imaginary technology. It beautifully captures the extent to which all language – including and perhaps especially scientific language, for all its pretensions otherwise – is inherently and unavoidably metaphorical. Du Bois transition from more or less mundane descriptions of physical objects

with one more swinging of the lever there swept down before the window a great tube, like a great golden trumpet with the flare toward us and the mouth-piece pointed toward the glit[t]ering sphere; laced round it ran silken cords like coiled electric wire ending in handles, globes and collar like appendages (824)

to the heightened and elusive description of their purpose introduces an ineffable tone that eases the next generic switch.

The great tube’s window displays a vision of New York that transforms before the viewers. The landscape becoming apocalyptically fantastical as the view rushes towards Pittsburg, where steel mills rise like cyclopean castles or ‘the Mills of the Gods’ and between them move obscure and terrifying Things – the ‘Things of this New World, the World of Steel’ (824).

A giant knight emerges. He is the Lord of the Golden Way, a disembodied Voice explains, and then tells in some detail a cod-epic story – part medieval romance, part allegory. (It is only loosely allegorical – there is not the direct one-to-one correspondence between manifest and latent content insisted upon by allegory proper, so it might be more accurate to think of it as a symbolic story, but only so long as you then don’t fall into the trap of expecting each symbol to directly correspond to one specific symbolised thing in a clearly delineated overarching scheme (because that would be allegory proper, horribly reductive and maddeningly dull).)

The Over-Man Sir Guess of Londonton captures the Witch Knowal – the wife of the ogre Evilhood – and she tells him of ‘the dark Queen of the Iron Isles—she that of old came out of Africa’ (825) and who is held captive in the Pits of Pittsburg, along with her enchanted daughter, Princess Steel, fathered by the Sun-God . The Lord of the Golden Way agrees to help Guess rescue the Princess Steel from her enchantment in exchange for her treasure. This leads to inevitable conflict. Guess promptly falls in love with the freed Princess, but the Lord realises her treasure resides in her body:

her hair is silver and her eyes are golden, and … mayhap there be jewels crusted on her heart. (828)

Guess is defeated, and as the Princess watches over her fallen lover, the Lord of the Golden Way begins to spin strands of her hair, which is the steel upon which the modern world is built. The San Franciso and Valparaiso earthquakes of 1906 are signs of her rage at the Lord of the Golden Way and she warns him

I watch and ward above my sleeping Lord till he awake and then woe World! when I shake my curls a-loose. (829)

On this note – presaging the dire consequences of industrial modernity, of capitalist and colonial and gendered exploitation, which include the violent overthrow of such a world – the vision ends.

The wife has seen none of this because, a little troublingly, the megascope ‘was not tuned delicately enough for her’ (829). (Even in The Dark Princess, Du Bois tends to push Princess Kautilya, one of the key members of the revolutionary Committee, into domestic roles.)

The couple make a hasty exit.

In the PMLA, ‘The Princess Steel’ is introduced by Britt Rusert and Adrienne Brown, who are currently co-editing a collection of Du Bois’s sf, fantasy, mystery and crime fiction. The story is locked behind the journal’s pay-wall – but there are bound to be people out there whose universities have institutional access.

be squeezed into the suitcase. As might D.O. Fagunwa’s Forest of a Thousand Daemons: A Hunter’s Saga (1939), translated by Wole Soyinka(!) – the first Yoruba-language novel, said to be an influence on Tutuola, not least in its fantastical landscape in which the supernatural is as real and present as the natural world.

be squeezed into the suitcase. As might D.O. Fagunwa’s Forest of a Thousand Daemons: A Hunter’s Saga (1939), translated by Wole Soyinka(!) – the first Yoruba-language novel, said to be an influence on Tutuola, not least in its fantastical landscape in which the supernatural is as real and present as the natural world. – satirical alternate history in which Africans have colonised a swampy Europe full of idle, childish, pallid natives

– satirical alternate history in which Africans have colonised a swampy Europe full of idle, childish, pallid natives – according to reviewers it is ‘Blade Runner in Africa with a John Coltrane soundtrack’ that ‘transfigures harsh reality with a bounding, inventive, bebop-style prose’ and depicts ‘a world so anarchic it would leave even Ted Cruz begging for more government’

– according to reviewers it is ‘Blade Runner in Africa with a John Coltrane soundtrack’ that ‘transfigures harsh reality with a bounding, inventive, bebop-style prose’ and depicts ‘a world so anarchic it would leave even Ted Cruz begging for more government’ – YA urban fantasy in which Cape Town provides a home for magical refugees

– YA urban fantasy in which Cape Town provides a home for magical refugees – contains five novellas by Tade Thompson and Nick Wood, Mame Bougouma Diene, Dilman Dila, Andrew Dakalira, and Efe Tokunbo Okogu

– contains five novellas by Tade Thompson and Nick Wood, Mame Bougouma Diene, Dilman Dila, Andrew Dakalira, and Efe Tokunbo Okogu