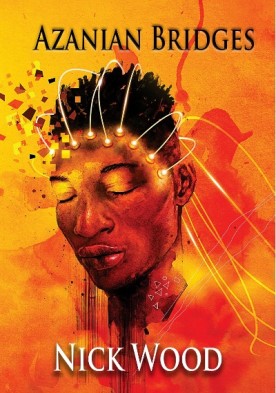

Azanian Bridges is a neat little thriller, set in more or less the present-day South Africa but in a world in which Apartheid continues. A quick and compelling read, it does a couple of rather cunning things.

Azanian Bridges is a neat little thriller, set in more or less the present-day South Africa but in a world in which Apartheid continues. A quick and compelling read, it does a couple of rather cunning things.

The first is its choice of alternate history premise.

There are a number of African alternate histories which invert or rewrite elements of European colonialism (e.g., Abdourahman A. Waberi’s In the United States of Africa (2006), Africa Paradis (Sylvestre Amoussou 2006) – and Nisi Shawl’s Everfair (2016) to look forward to).

There is a future history imagining the conditions for the emergence of something akin to Apartheid (Arthur Keppel-Jones’s When Smuts Goes: A History of South Africa from 1952 to 2010, first published in 2015 (1947)).

There is an array of near-future thrillers that anticipate the end of Apartheid (Anthony Delius’s The Day Natal Took Off (1960), Gary Allighan’s Verwoerd – the End (1961), Iain Findlay’s The Azanian Assignment (1978), Randall Robinson’s The Emancipation of Wakefield Clay (1978), Andrew McCoy’s The Insurrectionist (1979), Larry Bond’s Vortex (1981), Nadine Gordimer’s July’s People (1981), Frank Graves’s African Chess (1990)).

And there is an alternate history with the brilliant premise of aliens arriving in the skies over Johannesburg during the Apartheid era, although sadly District 9 (Blomkamp 2009) doesn’t have the faintest idea what to do with it. (Read Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon (2014) instead.)

But, as far as I know, Azanian Bridges is the first story to project Apartheid beyond 1994.

In doing so, Wood sketches in some sly geopolitical changes. The Soviet Union did not withdraw from Afghanistan in 1989, but has spent thirty years ‘haemmorrhaging men into their Afghan ulcer’ (31). Perestroika and glasnost seem not to have happened, and the USSR is intact, apparently governed by generals. The Berlin wall has not fallen, nor has the Eastern bloc collapsed. Consequently, ‘the old anti-communist arguments for supporting’ South Africa (163) held sway rather longer among Western powers, and it comes as little surprise that Bush and Blair were both supporters of the Apartheid regime. But now President Obama – along with his ally, the US-backed mujahideen leader Osama bin Laden – are involved in peace talks with the Soviets. The Cold War might finally be limping into its terminal phase, and with weakening Soviet influence in Africa, China is investing heavily across the continent. Meanwhile, in a South Africa ruled by President Eugène Terre’Blanche’s Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging, Mandela did not leave Robben Island and FW de Klerk is still in prison for trying to bring Apartheid to an end in the 1980s.

All of which is sketched in with greater economy than I have just managed, not least because the layers of paranoid security and firewalling significantly restrict all South Africans’ access to the internet and other global media. Phones with cameras are also banned since they are a ‘potentially easy source of troubling video’ (45) – a nice touch that captures the novel’s relevance to our #blacklivesmatter times.

The second (and really really) cunning thing that Wood does is make a connection between the new experimental technology introduced into this alternative near-present and the form his narrative takes: the Empathy Enhancer allows one to experience the experience of others, and vice versa; the novel’s chapters alternate between Sibusiso Mchunu, a young amaZulu on the edges of anti-Apartheid struggle who is deeply traumatised when a friend dies in his arms, shot to death by the police at a protest, and the white (but as-yet not very committed) liberal, Dr Martin Van Deventer, the neuropsychologist treating Sibusiso and co-inventor of the Empathy Enhancer.

The security services want the EE device for use in interrogations. Anti-Apartheid groups want to use it to undermine the regime, person-by-person. It is not clear why the Chinese want it, but they do. So when Sibusiso goes on the lam with the device, and Martin sets out in pursuit, the alternating chapters set you up to expect a tensely intercutting thriller, as pursuers become the pursued.

And there are a number of tense sequences and suspenseful passages.

But Wood is playing a very different game, subverting the form to make the reader focus on the twin protagonists’ very different experiences of living in a racist state which sees them both, in different ways, as its enemies. This ranges from the most perilous things – run-ins with the security services – to the most quotidian: when Martin is told to destroy his cell phone so it can’t be used to trace him, he simply ‘grind[s] the phone under [his] heel’ (153); when Sibusiso’s phone is simply taken from him and tossed into the sea, he is ‘upset and angry’, in large part because ‘we have been taught to throw nothing away’ (129).

Such contrasts are the point of the novel.

Azanian Bridges itself is the Empathy Enhancer. Read it and weep.

Hi Mark,

Been reading your posts on African sci-fi, I keep seeing negative assumptions about District 9 (Blomkamp 2009), or of the director himself. The only evidence I have seen as to why his film direction wasn’t as worthy of other African sci-fi has been his national origin (you mentioned something about US/New Zealand/Australia)… I’m not sure how this discredits him as a visionary?

Of course, he was making a hollywood blockbuster and not a novel, but I’ve always seen him as a champion of bringing an ignored history to the 21st century masses.

-Tim

LikeLike

Hi Tim, my real problem with District 9 is its shockingly racist portrayal of Nigerians as criminal gangsters given to witchcraft and cannibalism. And while the film has a great premise – the arrival of aliens during the apartheid period – it does nothing with it. There is no sense of how the appearance of these others affected the late period and end of apartheid. So for me it has a lot of political potential but fails to follow through on nit; and it fails as sf by not being smart enough about its own central idea. (The US/NZ/Australia thing is about the production companies, not Blomkamp himself). I was also not especially impressed by Elysium (which is okay as a dumb blockbuster – and unlike District 9 it really does have a blockbuster budget) or Chappie (which is a bizarre mess, but not in a good way). But I do quite do like his early short films.

LikeLike