This post is based on a couple of old conference papers, delivered at Screen (2005) and ICFA 27 (2006), that I never had chance to develop further and forgot about until I stumbled on a draft the other day.

This post is based on a couple of old conference papers, delivered at Screen (2005) and ICFA 27 (2006), that I never had chance to develop further and forgot about until I stumbled on a draft the other day.

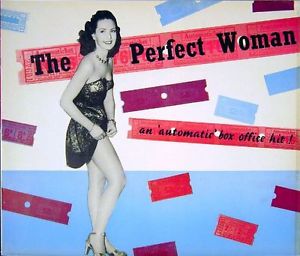

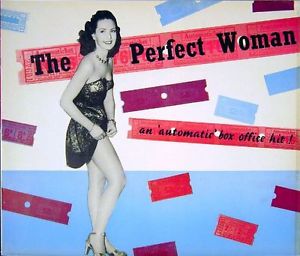

Bernard Knowles’ 1949 film The Perfect Woman is based on Wallace Geoffrey and Basil Mitchell’s play, which premiered September 11th 1948 at the Playhouse Theatre, and follows it quite closely. The dotty Professor Belmon (Miles Malleson) builds a robot called Olga (Pamela Devis), modelled on his niece, Penelope (Patricia Roc). He hires Roger Cavendish (Nigel Patrick), a penniless man about town, and his valet, Ramshead (Stanley Holloway), to field-test Olga by taking her out in society. Penelope, who has led a rather sheltered life, swaps places with Olga. The threesome book into the bridal suite at the Hotel Splendide. Rumours of Roger’s marriage soon reach his aunt, Lady Mary (Philippa Gill), who returns immediately from Paris. The farce escalates until Roger and Penelope realise they love each other. Their mutual declaration sends Olga, who for no clear reason cannot be allowed to hear the word ‘love’, haywire. She blows up, taking part of the hotel with her.

It is a lovely little film, and a rare example of the science fiction romantic comedy.

Many sf movies provoke laughter, and some – sf comedies – even intend to. Many sf movies also contain romance, but few are romances. And ‘sf romantic comedy’ is a vanishingly small category.

Undoubtedly, the film industry’s gendered assumptions about the audiences the two genres attract prevent the greenlighting of such projects, and thus reduce the likelihood of them even being proposed. But perhaps, too, there is an incompatibility in the generic logics of the dominant forms of sf and romantic comedy.

The romantic comedy narrative is typically intimate. Its characters often withdraw from the social realm to a green space or relatively hermetic equivalent. The genre’s spectacle is also intimate: a star couple talk to each other and, in close-up and luminously-lit, finally profess their love; those moments when William Powell and Myrna Loy enjoy each other’s martini-enhanced company, talking to each other but saying nothing in particular and certainly nothing of any narrative consequence. In contrast, however much sf tries to humanise its concerns, its narratives – global crises, interplanetary conflicts – do not happen on the scale of the individual, and its spectacle is environmental: human figures are there to provide a sense of the scale of the backdrop, of just how big the alien fleet is.

company, talking to each other but saying nothing in particular and certainly nothing of any narrative consequence. In contrast, however much sf tries to humanise its concerns, its narratives – global crises, interplanetary conflicts – do not happen on the scale of the individual, and its spectacle is environmental: human figures are there to provide a sense of the scale of the backdrop, of just how big the alien fleet is.

These are of course generalisations.[i]

Not all sf cinema is spectacular. Often for budgetary reasons, sf films sometimes tell smaller scale stories. For every dozen 50s drive-in movies in which an alien invasion takes the form of some guy in an old gorilla suit and a deep-sea diver’s helmet wandering around Bronson caverns, there is an sf movie in which smallness is about an intimate human scale: Liquid Sky (1982), The Brother from Another Planet (1984), Last Night (1998), Possible Worlds (2000), Chetyre (2005) and the recent ‘low-fi sci-fi’ trend. Moving past the dominant contemporary logic of sf-as-spectacle lessens the sense that sf and romantic comedy are necessarily antagonistic.

So I want to begin by considering The Perfect Woman in the light of Darko Suvin’s and Samuel Delany’s accounts of how sf works. Suvin defined sf as

a literary genre whose necessary and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment

He argued that

SF is distinguished by the narrative dominance or hegemony of a fictional “novum” (novelty, innovation) validated by cognitive logic

and that the

novum or cognitive innovation is a totalizing phenomenon or relationship deviating from the author’s and implied reader’s norm of reality.[ii]

The Suvinian sf text is one in which the author has imagined some materially plausible innovation, thought through all the implications of its introduction, and then written a story in which that altered world is presented in all its variety without ever necessarily explaining the root of the alteration.

In reality, few sf texts do this.

But there are some common variations on this ideal, such as the gadget story, common in the pre-World War 2 pulps, in which an astonishing device with all manner of implications and potential consequences is devised, operated briefly and then destroyed. This story type demonstrates the powerful conservativism of actually-existing sf, despite the radical potential Suvin and others find in it.

Actually-existing cinema is likewise conservative.

Generally incapable of proposing radical social transformation (it is more interested in robots and monsters than alternative social, political or economic structures), sf film often introduces a novum, whether a terminator or a man’s white suit, into a relatively hermetic social setting so as to briefly play out some of its implications before the possibility of radical transformation is shut down by the narrative reassertion of equilibrium. When following this structure, sf comes closer to the structure of romantic comedy – or at least permits a complementary structure to occur, with the restricted space/time of the novum’s presence paralleling romantic comedy’s green space (the nighttime woodland of Bringing Up Baby (1938)) or other delimited transitional space/time (the road – and several nights – of It Happened One Night (1934)).

This structural meshing of genres occurs in The Perfect Woman.

A novum – the android Olga – is introduced into an otherwise unchanged social setting (admittedly it matches neither the author’s nor the implied viewer’s but the conventional upper class milieu of West End farce, looking pre-World War 1 rather than post-World War 2). But rather than allowing the android to be introduced into this social realm, Penelope substitutes herself for the novum and thus transforms the hotel suite into a romantic comedy’s ‘green space’. Some potential implications of this new technology are hinted at, but the movie concentrates instead on the more intimate concerns of the stars falling in love; and as they declare their love, the android self-destructs, permitting the world to continue as if she had never existed.

Delany argues that different kinds of word-series are distinguished by their level of subjunctivity: reportage says this happened; naturalistic fiction could have happened; fantasy could not have happened; science fiction has not happened (which might include might happen, will not happen, have not happened yet, could have happened in the past but did not).[iii] He argues that as we learn the level of subjunctivity of the text, we simultaneously learn how to read the words from which it is constructed. An example he uses to clarify this idea is the expression ‘Her world exploded’. A romance novel’s clichéd description of emotional trauma might mean something different when describing Princess Leia.[iv]

Delany argues that the

point is not that the meaning of the sentences is ambiguous … but that the route to their possible mundane meanings and the route to their possible SF meanings are both clearly determined.[v]

However, the ambiguity of such a sentence is vitally important: just because it appears in an sf context does not mean that it must be read in its latter sense; there are more proximate determinants of meanings than genre, although those determinants themselves might be determined – enabled or constrained – by genre (although of course genre is simultaneously determined by how the sentence is read). And in this particular instance from Star Wars it can mean both things at once.

Delany is of interest because The Perfect Woman develops much of its humour through linguistic ambiguity, including some fairly racy doubles entendres and other systems of doubling, other proliferations and profligacies. I will outline some of these, before returning to the question of genre by asking, so who exactly is the perfect woman? Penelope or Olga?

The basic humour of double meanings comes from the fact that Olga must be given explicit verbal instructions; but she is programmed to respond to words regardless of the context in which they are uttered (she consistently ignores genre). And it is not only expressions like ‘hopping mad’, ‘get a kick out of it’ and ‘slap up’ that cause problems.

When Belmon’s housekeeper, Mrs Butters (Irene Handl), takes Olga on the tube, she enquires at the gate, ‘Is this right for Green Park?’ Olga, who is ahead of her, turns right and nearly walks straight into the gents’ loos.

This strand also involves Penelope-as-Olga deliberately obeying such accidental instructions, and Roger and Ramshead’s growing proficiency at working necessary instructions into conversation.

When Belmon hires Roger and Ramshead, he talks at length about a woman he has ‘made’ without ever mentioning that he means a robot. Bubbling below the surface is a sense of impropriety, of everything Belmon says in innocence being taken by the others to mean something else – the viewer knows the real meaning, but can enjoy their misinterpretation. The scene culminates in Belmon explaining that the field-test is to avoid embarrassment when he presents Olga to his fellow scientists: it would do no good to give her a big build up only to find that he has produced

a woman who can’t work.

Ramshead uncertainly responds,

a woman must work, if she’s a working woman, scrubbing and all that.

The meaning of ‘working woman’ shifts from ‘functioning robot’ to ‘woman engaged in work’ to ‘prostitute’; ‘scrubbing’ simultaneously evokes domestic labour and, possibly, a scrubber in the sense of slattern (although the OED’s first recorded usage of ‘scrubber’ in this way is not until 1958).

There is a similarly difficult to interpret moment later in the film when Olga smokes a cigarette and breathes out through her ears: was this a joke about fellatio in 1949? and, as in the fellatio joke, is this ability what makes her a candidate for the perfect woman?

There is a similarly difficult to interpret moment later in the film when Olga smokes a cigarette and breathes out through her ears: was this a joke about fellatio in 1949? and, as in the fellatio joke, is this ability what makes her a candidate for the perfect woman?

This euphemistic humour recurs. There are jokes about the delicacy of the mechanism, and about how beautifully built Penelope-as-Olga is. And when Mrs Butters, sozzled on sherry sits in Ramshead’s lap, he comments on her breath smelling of trifle.

Alongside euphemism is the unintended meaning, as when Belmon tells Roger

A child could work Olga. I’m sure you’ll get on with it.

The hotel is run by the Italian Farini (Fred Berger) and the guests are served by a Swiss waiter (David Hurst), leading to jokes about pronunciation and meaning, including confusion over the respective meanings of ‘to say’ and ‘to talk’. This strand begins when Ramshead tells Roger he has booked them into the Splendide.

Roger: Splendid.

Ramshead: Really, I always presumed it was pronounced splendide.

In a later exchange, ‘vase’ is pronounced three different ways – ‘vorze’, ‘varze’ and ‘vayze’ – in as many words.

When Lady Mary dismisses the waiter, saying

You needn’t wait.

He mournfully replies

That’s what I’m for.

When serving Penelope a second bowl of soup, he gets into an argument about whether or not she wants any more:

But sometimes when a lady says ‘no’ it is ‘yes’ she is meaning so ‘no’ means ‘yes’, no?

All of this wordplay depends upon the profligacy of signs, of signifiers producing multiple signifieds. And by constantly foregrounding linguistic ambiguity, The Perfect Woman draws attention to the contextual derivation of meaning and offers a fantasy of plenty during post-war scarcity. The latter is suggested by the anachronistic upper class milieu. Roger’s penniless condition, his fully-extended overdraft, and his aunt’s refusal to pay his monthly allowance are comic conventions that do nothing to exclude him.

When ordering dinner, Ramshead asks for just

When ordering dinner, Ramshead asks for just

something light. Say some soup, fish, chicken, joint, sweet, cheese, dessert, coffee, anything else that occurs to you … Oh yes, something to drink. A bottle of scotch, two dozen bottles of beer, another bottle of scotch, a small fizzy lemonade, and a bottle of scotch.

At the prospect of food, Penelope licks her lips in a peculiarly lascivious close-up; the shot is more or less repeated when Farini describes dessert.[vi]

And much is made of the fabulous underwear bought for Olga but modelled by Penelope – its luxury and ‘femininity’ contrasting strongly with Olga’s rather more fetishistic underclothing.

And much is made of the fabulous underwear bought for Olga but modelled by Penelope – its luxury and ‘femininity’ contrasting strongly with Olga’s rather more fetishistic underclothing.

Unlike the Ealing comedies Hue and Cry (1947) and Passport to Pimlico (1949), the war’s devastation of London is hidden, an eradication of history which even includes changing the waiter’s nationality from German-Swiss to Swiss – in another gesture of profligacy, he is called Wolfgang Wilhelm Winkel, the second.

Unlike the Ealing comedies Hue and Cry (1947) and Passport to Pimlico (1949), the war’s devastation of London is hidden, an eradication of history which even includes changing the waiter’s nationality from German-Swiss to Swiss – in another gesture of profligacy, he is called Wolfgang Wilhelm Winkel, the second.

One might regard all this as a consolatory fantasy – a West End big rock candy mountain – in the way it is often asserted that 1930s musicals offered escape from the lived reality of the Depression. Read in this way, and through a lens provided by Andreas Huyssen’s discussion of the two Marias in Metropolis (1927), a central part of this fantasy is the destruction of the machine.[vii] The twinning of Penelope and Olga enables a separation of woman-as-nature from woman-as-technology. And the bridal suite functions as a romantic comedy green space – it is where Penelope clearly belongs and from which Olga, who sparks energy and manically goosesteps around the suite when she hears the word ‘love’, must be ejected.

This decision, the film’s nomination of Penelope rather than Olga as the perfect woman, requires examination.

Penelope asks her uncle

why did you make it like me?

He replies

Well, my dear, I call her the perfect woman … where else should I find such a model? It was either you or Mrs Butters.

When Roger asks him why he calls Olga the perfect woman, Belmon explains

Well, she does exactly what she’s told. She can’t talk. She can’t eat. And you can leave her switched off under a dust sheet for … weeks at a time.

Roger and Ramshead nod approval.

Earlier, Belmon says that Penelope is

After all … only just another young woman. Flesh and blood and a little calcium … there are millions of them. Mass production. There’s only one Olga.

As with many robotic creations, and with doubles since Hoffman and Poe, this overt reference to mass production in relation to humans evokes the spectre of mechanical reproduction as capital cyborgises and homogenises the subject, as relations between people take on the form of relations between things.

Silvia Federici argues that

the human body and not the steam engine, and not even the clock, was the first machine developed by capitalism.[viii]

And what Marxist accounts of the transition to capitalism have often failed to recognise are the ways in which women were removed from the realm of ‘productive work’. Both the domestic and reproductive labour they then undertook were normalised as female activities and as activities which should not be counted as part of the labour necessary for the extraction of surplus-value, despite being essential to the reproduction of labour power both in terms of enabling the labouring man to recuperate and of having children.

It is not then surprising to find jokes about ‘working women’ and ‘scrubbers’, or layers of misogyny underlying Belmon’s lines about the perfect woman. These lines locate the film within a clear sf tradition, exemplified by Lester Del Rey’s ‘Helen O’Loy’ (1938) and Kate Wilhelm’s ‘Andover and the Android‘ (1963), in which a robot woman is preferred to any human female. A more atypical story in this vein is CL Moore’s ‘No Woman Born’ (1944), a sort-of feminist/anti-humanist story in which the cyborged female protagonist loves the superiority her new form gives her.

The Perfect Woman, by destroying the foreign/industrial/bound female body hidden by dustsheets, constrictive underwear and heavy macs, offers up the female body as a sensuous object, part of a ‘natural’ plenitude in the scarcity of post-war Britain. This, then, is why Olga cannot hear the word ‘love’ without going haywire. If domestic labour is treated as a person instead of a thing, patriarchal-capital logic is under threat. The only thing to do is to design the robot to malfunction should such a thing happen, saving the system and punishing the offending man with the loss of his robot. By thus restoring a ‘natural’ order of class and gender, it suggests that the green space need never end.

The Perfect Woman, by destroying the foreign/industrial/bound female body hidden by dustsheets, constrictive underwear and heavy macs, offers up the female body as a sensuous object, part of a ‘natural’ plenitude in the scarcity of post-war Britain. This, then, is why Olga cannot hear the word ‘love’ without going haywire. If domestic labour is treated as a person instead of a thing, patriarchal-capital logic is under threat. The only thing to do is to design the robot to malfunction should such a thing happen, saving the system and punishing the offending man with the loss of his robot. By thus restoring a ‘natural’ order of class and gender, it suggests that the green space need never end.

But this preference is compromised by Patricia Roc’s performance as Penelope, another of the film’s areas of doubling and ambiguity. She is most enjoyable to watch when she slips between robot and human, when the viewer is invited into complicity with her masquerade. The concluding ‘falling in love’ is as perfunctory as it is compulsory. There is therefore the prospect of her popping out from behind the facade of the normalised gender role of Roger’s wife.

But this preference is compromised by Patricia Roc’s performance as Penelope, another of the film’s areas of doubling and ambiguity. She is most enjoyable to watch when she slips between robot and human, when the viewer is invited into complicity with her masquerade. The concluding ‘falling in love’ is as perfunctory as it is compulsory. There is therefore the prospect of her popping out from behind the facade of the normalised gender role of Roger’s wife.

If, as Federici argues, the role of the wife is to reproduce labour, to be subsumed into and as part of the mechanism by which surplus-value is extracted, Penelope has already demonstrated that she lives in excess of such constraints – even if this excess is articulated through a much more post-feminist-seeming making-invisible of labour through fantasising about consumption.

Notes

[i]

The extent of their validity might be judged by considering the spate of overblown sf family melodramas such as Deep Impact (1998), Mission to Mars (2000), the entire Star Wars series, every sf film Spielberg ever made. This turn to melodrama – which is as often about fathers and sons as it is about romance – can be seen as a way of humanising the spectacular scale made possible by CGI, of turning masculine-gendered genres into less masculinely-coded ones. This logic also applies to such movies as Titanic (1997) and Pearl Harbor (2001), which use the technologies of sf cinema to construct melodramatic spectacles. Perhaps another reason for these movies’ relative success is that in melodrama, like sf, the environment signifies. It is spectacular and has meaning.

[ii]

Darko Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), pp.7-8, 63, 64; italics in original.

[iii]

See Samuel R. Delany, ‘About Five Thousand Seven Hundred and Fifty Words’, The Jewel-Hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction (Elizabethtown: Dragon Press, 1977), pp.33-49.

[iv]

See Samuel R. Delany, ‘The Semiology of Silence: The Science Fiction Studies Interview’, Silent Interviews: On Language, Race, Sex, Science Fiction, and Some Comics (Hanover: Wesleyan University Press/University Press of New England, 1994), pp.21-58.

[v]

Delany, ‘The Semiology of Silence’, p.27.

[vi]

Several other pieces of business are repeated, with variations: because she does not believe Roger, Lady Mary sticks a pin in Penelope and then later in Olga. When Roger and Penelope first swoon at each other and make as if to kiss, Mrs Butters, who has just arrived, shouts stop at Olga. Misunderstanding, they stop and look around, and Penelope kisses Roger on the cheek; this gag is repeated, only the second time it is Roger who kisses Penelope.

[vii]

Andreas Huyssen, ‘The Vamp and the Machine: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis’, After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), pp.65-81.

[viii]

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2004), p.146; italics in original.

Some 700 years later, on human-colonised Venus, in Henry Kuttner’s Fury (1950, co-written with uncredited CL Moore):

Some 700 years later, on human-colonised Venus, in Henry Kuttner’s Fury (1950, co-written with uncredited CL Moore): You probably think getting hold of an old omnibus of Edmond Hamilton’s Star Kings books is not much of an accomplishment. Nothing to boast about.

You probably think getting hold of an old omnibus of Edmond Hamilton’s Star Kings books is not much of an accomplishment. Nothing to boast about. Now, I have nothing against East End Sagas, whether gripping – as it claims – or not. But it was not what I wanted. So I set the returns process in motion and requested they replace it with the book I ordered. They acted with unexpected promptness, dispatching a replacement the same day. Of course, instead of replacing it with a copy of Chronicles of the Star Kings, they replaced it with a copy of Carol Rivers’s gripping East End saga Lizzie of Langley Street.

Now, I have nothing against East End Sagas, whether gripping – as it claims – or not. But it was not what I wanted. So I set the returns process in motion and requested they replace it with the book I ordered. They acted with unexpected promptness, dispatching a replacement the same day. Of course, instead of replacing it with a copy of Chronicles of the Star Kings, they replaced it with a copy of Carol Rivers’s gripping East End saga Lizzie of Langley Street.

The only problem is, I no longer have any fucking clue what I wanted it for in the first place.

The only problem is, I no longer have any fucking clue what I wanted it for in the first place.