Reading The Great Writers, part five

Back when I started this, I was pretty sure

- it wouldn’t be listy;

- some point would have emerged; and

- I would end by announcing my plan to read all the still-unread titles in the series in 2024.

Such optimism!

Looking back, it is funny – to me at least – to see how some of my ongoing work patterns came about. My partner is constantly amused/appalled at how much time I devote, when working on some project or other, to reading absolutely everything. For example, This Is Not A Science Fiction Textbook (forthcoming) contains 51 lists of 5 recommended books. I had already read about 140 of them so was confident they were appropriate examples for the multiple dimensions/agendas of the project. But none of the other 115, regardless of their critical reception, made it onto a list until I’d read it to ensure it did what we wanted it to do. Which of course also involved reading and rejecting some titles and then reading alternatives. Add in the reading to select books for the contributor chapters, and the reading for the chapters I wrote, and in total, I read 200 or so books for this one project . Which is part of the reason it took a year and half to complete, rather than the six months I’d imagined. (There are also 35 lists of 5 recommended films or TV shows, but that only involved needing to watch 11 things.)

Next year I am giving several talks on climate fiction, but at least I’ve had the good sense to look specifically at short fiction. Although not enough sense to come up with a promised sample size of less than 200 stories.

When I’m caught up in such obviously mad behaviour, I tend to think of it as doing due diligence. But really it is a kind broken-ness rooted in class anxiety. The need to feel not a sham. (I think this also explains the earnest tone of much that I write, and the flippancy with which I tend to present my work. Constantly trying to prove I’ve earned my stripes, desperately trying to please.)

(Academic friends, I might sometimes be the dreaded reader 2, I’m sorry, but at least I will have (re)read and/or (re)watched your primary texts before writing my report recommending changes that directly contradict everything reader 1 said.)

***

As I looked back over all those years of reading, I thought I would find myself wishing that it had been easier to find my way. And for sure, there are some things I would rather not have gone through (and I don’t just mean Henry James’s later novels, though they are on the list).

But then I think of all the moments (and days and weeks and years) of kindness and generosity I would have missed out on from all those (often somewhat bemused) teachers, librarians, friends, bookstore workers…

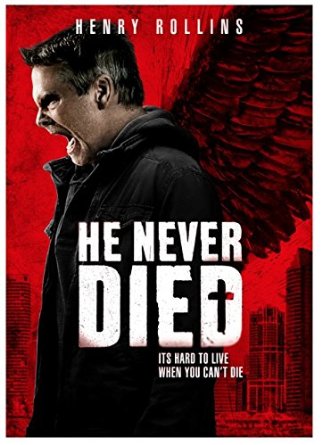

(And all those moments of absurdity, too. I mean, who reads Sir Charles Grandison when there’s no pressure on them to do so? Who contemplates getting inked with a Moby-Dick barcode? (My professorial inaugural lecture, which should finally happen late next spring, will climax with the utterly inappropriate unveiling of a far more visible and even more absurd tattoo. Just need to work out the fanfare music. (I’ll definitely enter like a boxer through dry ice and dancing spotlights to Rollins Band’s ‘Shine’.) Just need to schedule getting the ink done at the right time once the date of the lecture is finalised.))

Part of my motivation as a teacher and my commitment to working in the less privileged parts of the sector has been to try to make it easier for working class and other marginalised students to find their feet at university, to navigate institutions not designed for them and cultures that are new to them, and to become confident about their own worth. (Although the long war on HE makes that harder every year, as of course has my own becoming-middle-classness and, ironically enough, the cultural capital it entails. Oh, and getting old and being perpetually exhausted by the job.)

On some level, of course, this commitment and motivation is inspired by that Oxford interview wanker. No one should have to go through that sort of thing. But it is much more rooted in the actions of those who, with no obligation to care, cared.

I just read an interview with my friend (and, as this quote suggests, a role model to strive and fail and strive to live up to) Tom Moylan, in which he says

First and foremost, I’ve always considered my primary role to be that of a teacher (with research and writing necessary for good teaching) and not that of an alienated ‘academic’. I consider teaching to be a matter of imparting knowledge in the context of facilitating with compassion a learning process that helps each individual break with their normative development and come to see the world freshly in order to develop a responsible sense of their place and path in that world.

Could you imagine if universities were actually organised to encourage and support us to do that? Rather than making us squeeze it in around all the bullshit?

***

But I guess the real reason you’ve hung around this long – if you have, which of course you have otherwise you wouldn’t be reading this bit – is to find out whether I will read those last 22 titles next year.

The answer was a definite ‘yes’ back when I started thinking about The Great Writers, but now it is more of a ‘probably’.

I’m not sure I want to spend much more of my life grinding through unrewarding books. But the only way to find out if they are unrewarding is to give them a go, and I do already have copies of ten of them (though one is in a box somewhere and thus not in this picture).

Monmouthshire libraries can provide another eight, and my university library another one on top of that.

Which means I’d only have to buy three books:

Greene’s The Comedians, which is fine with me,

but,

oh

for

fuck’s

sake,

James’s Portrait of a Lady and Waugh’s Vile Bodies?

It is entirely possible your mother has told you that

It is entirely possible your mother has told you that  There is a moment in Lee Scratch Perry’s Vision of Paradise (2015), when Volker Schoner shows some poor journalist asking Perry what his typical day is like and then sitting there bemused as ihe mprovises a rambling reply, which ultimately comes down to something like ‘I wake up and see what’s on my to-do list’. But it doesn’t sound anywhere near as mundane as that. (The haplessness of the journalist reminded me of that time The Word sent some child to interview Henry Rollins, and she asked him what music he listens to. He describes playing the first four Black Sabbath albums back-to-back; the journo, who clearly does not know Black Sabbath other than as the name of some band to whose wax cylinders her grandpa used to listen, asks ‘what is that like?; Rollins replies, ‘Dunno, have you ever been killed?’) This is quite a cunning move by Schoner, a sneaky displacement of his own bemusement – but he is clearly also often baffled by his subject.

There is a moment in Lee Scratch Perry’s Vision of Paradise (2015), when Volker Schoner shows some poor journalist asking Perry what his typical day is like and then sitting there bemused as ihe mprovises a rambling reply, which ultimately comes down to something like ‘I wake up and see what’s on my to-do list’. But it doesn’t sound anywhere near as mundane as that. (The haplessness of the journalist reminded me of that time The Word sent some child to interview Henry Rollins, and she asked him what music he listens to. He describes playing the first four Black Sabbath albums back-to-back; the journo, who clearly does not know Black Sabbath other than as the name of some band to whose wax cylinders her grandpa used to listen, asks ‘what is that like?; Rollins replies, ‘Dunno, have you ever been killed?’) This is quite a cunning move by Schoner, a sneaky displacement of his own bemusement – but he is clearly also often baffled by his subject.