It has always been there, always been part of my love of Lowry, but only now has it become clear. Our context summons it, gives it voice.

The world that is being made over into a mire, a midden, clogged with the filth unleashed by capital’s emancipation of sunlight captured long ago, its unleashing of carbon compressed and incarcerated far beneath the surface.

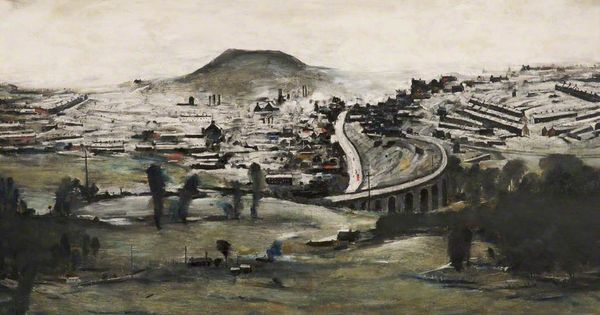

(In passing, I love the tiny splash of red, the bus coming down the hill; I also love the outrage of several Salford councillors when the city spent 54 guineas on the first of the seascapes below because there was nothing in the picture, not even a boat.)

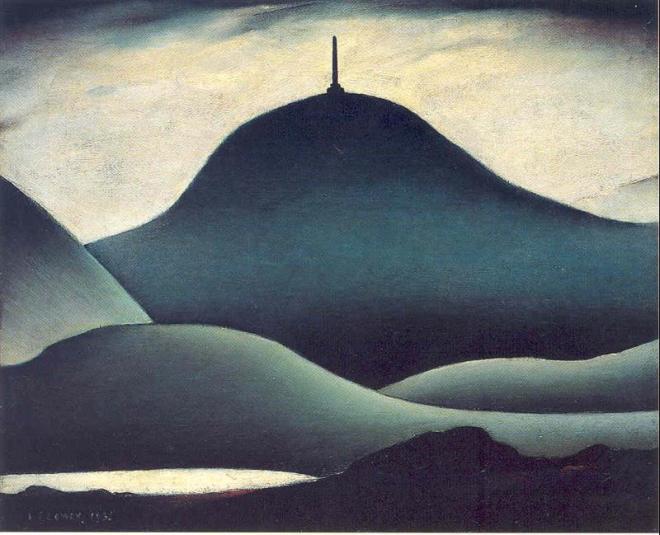

But Lowry, for all his matchstick men and matchstick cats and dogs, also painted the world without us. A world desired, a world restored, in which we are a memory at most – a mark on the land, a residual trace of that which has passed, as in this impish female nude called ‘The Landmark’.

Such towers outlast us, move off into abstraction as we recede from being.

And beneath them, sometimes, there is the sea.

Lowry often spoke of the sea in relation to loneliness, but his seascapes move beyond that particular personal psychological sensibility. They are images of the world in which human categories, our separations of it all into distinct things, no longer hold.

Reification revoked.

Our spectrality, our deathliness, always there in the portraits and figures, attenuates, fades, disperses.

The tide rises.

We are gone.

The rather striking Lowry theatre/gallery sits on the edge of one of those windswept plazas contemporary regeneration schemes, vaguely recalling a trip to Italy, insist upon, regardless of climate. Opposite is the insulting Lowry Outlet Mall. And all around are luxury apartment blocks, astonishingly mundane and uniformly balconied, again regardless of actual fucking climate.

The rather striking Lowry theatre/gallery sits on the edge of one of those windswept plazas contemporary regeneration schemes, vaguely recalling a trip to Italy, insist upon, regardless of climate. Opposite is the insulting Lowry Outlet Mall. And all around are luxury apartment blocks, astonishingly mundane and uniformly balconied, again regardless of actual fucking climate. But we were there to see the Lowry paintings, only recently abducted from the Salford Museum and Art Gallery (opened in 1850, it was the first free public library in the UK). The exhibition is not as substantial as the one we went to at Tate Britain, but is probably more representative of Lowry’s range, and there weren’t twenty or thirty people between you and each picture.

But we were there to see the Lowry paintings, only recently abducted from the Salford Museum and Art Gallery (opened in 1850, it was the first free public library in the UK). The exhibition is not as substantial as the one we went to at Tate Britain, but is probably more representative of Lowry’s range, and there weren’t twenty or thirty people between you and each picture.