From 18 June to 20 October 2013, the Porter gallery in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum was home to Memory Palace. Sponsored by Sky Arts Ignition, it is the first graphic arts exhibition at the venue in over a decade. It features one eponymous novella by Hari Kunzru (published separately) and twenty installations by as many artists or studios, and attempts to see “how far [you can] push the format and still call it a book,” to provide “an experiential reading format for a story,” to “create an exhibition that can be read’ (Newell and Salazar, “Curating a Book,” Memory Palace 84, 85). It is also a work of sf.

Curators Laurie Britton Newell and Ligaya Salazar commissioned Kunzru to outline a story that would then be developed in collaboration with the artists, who would be co-creators rather than mere illustrators: Abäke, Peter Bil’ak, Alexis Deacon, Sara De Bondt studio, Oded Ezer, Francesco Franchi, Isabel Greenberg, Hansje van Halem, Robert Hunter, Jim Kay, Johnny Kelly, Erik Kessels, Na Kim, Stuart Kolakovic, Frank Laws, Le Gun, CJ Lim, Luke Pearson, Stefanie Posavec, Némo Tral, Henning Wagenbreth, Mario Wagner, and Sam Winston. This process is recounted in Hunter’s dialog-free, short graphic comic, “Making Memory Palace,” appended to Kunzru’s novella.

The British-Indian Kunzru, a former magazine journalist, who wrote about travel, music, culture, and technology, is, like David Mitchell, one of that generation of authors relatively untroubled by genre-policing. His second novel, Transmission (2005), is about a computer virus, and reads like a slimmed-down, nearer-future version of Ian McDonald’s River of Gods (2004) spliced together with one of William Gibson’s Bigend novels; his fourth and most recent novel, the historically-sprawling Gods without Men (2012), includes UFOs and aliens, kinda. A rather trendy literary author, his first novel, The Impressionist (2003), attracted a £1 million+ advance, and he has won several major awards and prizes. The central concerns of his particular brand of popular, not exactly demanding postmodernism, sometimes described as “hysterical realism” or “translit,” are non-linearity and connectivity. Kunzru’s commissioning by Sky Arts is, then, relatively unsurprising (especially as he also used to be a presenter on The Lounge, Sky TV’s own electronic arts program).

His co-creators are rather less well known. Intriguingly, in their brief biographies at the end of the Memory Palace book, not one of them self-describes as an artist. They are all graphic designers, graphic artists, typographers, illustrators, comics artists, book designers, creative directors, art directors, editors, and/or architects. One is left with a strong sense of a smug and slightly shadowy commercial world of professionals, talented but perhaps a bit glib, for whom this is just another commission to be turned in on budget and on time. This perhaps explains why the exhibition’s satirical attack on neo-liberal hegemony and state-imposed regimes of austerity and amnesia is so muted.

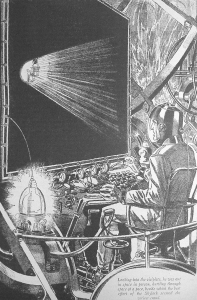

Kunzru’s novella, Memory Palace, is set in a post-apocalyptic London. A magnetic storm destroyed the global information infrastructure and brought the Withering, a post-literate Dark Age of totalitarian theocracy, in which Westminster is known as Waste Monster, and other moderately amusing sub-Riddley Walker (1980) wordplay thrives. The Thing (as the council of leaders is known) wants to bring about the Wilding, a future in which the remnants of humanity will live in harmony with nature. The Thing has outlawed writing and recording, thereby criminalizing the Memorialists, those who are devoted to collecting and recollecting the past, whom they now hunt. Appropriately, then, the story, while nicely written and more than competent, stirs with faint echoes: of post-apocalyptic fiction by John Wyndham, John Christopher, and Walter M. Miller; of the television series Survivors (UK 1975-1977) and the coda to the film Threads (Jackson UK/Australia/US 1984); of M. John Harrison’s seedy bedsit entropy, China Miéville’s rejectamentalism, and Evan Calder Wood’s salvagepunk.

The book version of Memory Palace is, as one would expect from such a project, a gorgeous object, lavishly illustrated with selected work from the exhibition and pictures of the physical and electronic installations. If you have read the book, though, the exhibition itself is a little disappointing (I cannot gauge what it would be like to see the exhibition before, or without, reading the book). Le Gun’s life-size model of what someone from the post-apocalypse imagines an ambulance to have looked like – part medicine show, part museum of curiosities, drawn by wolves and driven by a Día de Muertos cross between Baron Samedi and the Child Catcher – is impressively detailed, as is Jim Kay’s reliquary cabinet devoted to Milord Darwing, the author of Origin of the Species (1859), who is misremembered as a rogue GM scientist. In contrast, Oded Ezer’s eight short films, looped on eight separate screens, are all concept with little art, and Erik Kessel’s enormous temple built from bundles of newspapers and advertising fliers, recalling the pre-apocalyptic religious ritual of

as is Jim Kay’s reliquary cabinet devoted to Milord Darwing, the author of Origin of the Species (1859), who is misremembered as a rogue GM scientist. In contrast, Oded Ezer’s eight short films, looped on eight separate screens, are all concept with little art, and Erik Kessel’s enormous temple built from bundles of newspapers and advertising fliers, recalling the pre-apocalyptic religious ritual of  Recycling, has even less art and barely even a concept. The more straightforward illustrations – whether blown up on large light boxes (Tral), arranged in a narrative thread on a white wall so you have to move to follow them (Pearson), or presented on zinc letterpress plates (Winston) – do benefit from exhibition. And it is quite pleasing – after all the corporate profligacy, the privatization and militarization of public spaces, the peonage of cleaners and others, the jingoism and spitefulness, that the London Olympics involved – to see the stadium reduced to slums (Tral) and Anish Kapoor and Arups’ 115-meter tall ArcelorMittal Orbit, a kind of flying spaghetti Eiffel Tower, being ceremonially burned to the ground (Greenberg).

Recycling, has even less art and barely even a concept. The more straightforward illustrations – whether blown up on large light boxes (Tral), arranged in a narrative thread on a white wall so you have to move to follow them (Pearson), or presented on zinc letterpress plates (Winston) – do benefit from exhibition. And it is quite pleasing – after all the corporate profligacy, the privatization and militarization of public spaces, the peonage of cleaners and others, the jingoism and spitefulness, that the London Olympics involved – to see the stadium reduced to slums (Tral) and Anish Kapoor and Arups’ 115-meter tall ArcelorMittal Orbit, a kind of flying spaghetti Eiffel Tower, being ceremonially burned to the ground (Greenberg).

Newell and Salazar write that “Unlike reading a printed book, visiting an exhibition is not usually a linear experience” (85). In this case, however, the layout of the space, and the clearly marked entrance and exit, do produce a linear exhibit, whereas reading the book, with its out-of-order narrative and illustrations that tempt one to flick back and forth between them, is more successfully non-linear. Consequently, I would recommend the book over the exhibition, especially as it is available from online stores for less than £10, and unless you live in South Kensington (or “South Keen Singtown,” as it will be known during the Withering), getting to and seeing the exhibition will cost you more than that.

A version of this review appeared in Science Fiction Studies 121 (2013), 596–8.