This is a slightly different version of an overview essay I was invited to write for the SFRA Review – the published version, along with other goodies, can be found in the pdf of # 311 (Winter 2015). There are updates here and here.

In almost every imaginable way, I am not qualified to write this piece. I am neither an Africanist nor an expert on African literatures and cultures, and my English degree is sufficiently ancient (and Leavisite) as to have been completely untroubled by critical engagement with world literature, orientalism, postcolonialism, diaspora, globalization, hybridity, the subaltern, and so on. However, thanks to the patience and generosity of many others who made the learning curve of editing the 2013 “Africa SF” issue of Paradoxa rather less steep than it otherwise would have been, there are some things I can pass on. As with that project, this essay is intended as an invitation – to engage with unfamiliar writers and texts, to broaden our vision of sf, and to look together to a global future.

In almost every imaginable way, I am not qualified to write this piece. I am neither an Africanist nor an expert on African literatures and cultures, and my English degree is sufficiently ancient (and Leavisite) as to have been completely untroubled by critical engagement with world literature, orientalism, postcolonialism, diaspora, globalization, hybridity, the subaltern, and so on. However, thanks to the patience and generosity of many others who made the learning curve of editing the 2013 “Africa SF” issue of Paradoxa rather less steep than it otherwise would have been, there are some things I can pass on. As with that project, this essay is intended as an invitation – to engage with unfamiliar writers and texts, to broaden our vision of sf, and to look together to a global future.

But can we speak of “African sf”?

Africa covers nearly 12 million square miles and has a population of more than a billion (over 20% of the Earth’s land surface and 15% of its population). It stretches from the northern temperate zone to the southern temperate zone and contains, in effect, 65 countries. Its peoples speak somewhere between 1000 and 2000 languages (and multilingualism is commonplace). In the light of such numbers, the adjective in “African sf” runs significant risks: of homogenizing diversity; of creating a reified, monolithic image of what it might mean to be “African”; of ghettoizing the sf of a continent as some kind of subset or marginal instance of a more “proper” American or European version of the genre; of patronizing such sf as somehow not yet fully formed, “developing” rather than “developed”; of separating such fiction from the wider culture(s) of which it is a part; of colonizing such cultural production by seeing it not through its own eyes but through those of Americans and Europeans.1 In teaching African sf, one way to avoid some of these problems might be to focus more closely on a single African country, enabling a more detailed and nuanced exploration of a particular culture (or set of intersecting cultures within that nation), but hitherto only South Africa and Nigeria have really produced enough sf in English for that to be feasible.

There are vast differences between – and within – North and sub-Saharan Africa. Across the continent, the influence of Arabic, European, Islamic, and Christian cultures has played out in myriad ways, as have colonialism, postcolonialism, and neo-colonialism. There are important distinctions to be drawn between – and within – indigenous and settler cultures, both in Africa and in diaspora. There are complex questions to be asked of the many hybridities thrown up at the lived interfaces and interweavings of these cultures and identities.

For example, at what point does an immigrant “count” as an African, or an émigré cease to “count” as one? Should Manly Wade Wellman, that stalwart of the US fantastic pulps from the late 1920s onwards, who was born in what is now Angola, be considered an African sf writer? How about Doris Lessing? She was born in Persia in 1919, lived in Southern Rhodesia from 1926-1949, before settling in the UK, where most of her fiction was written. How about Buchi Emecheta, born in Nigeria in 1944 but resident primarily in the UK from 1962? Or Scottish-born Jonathan Ledgard, the East African correspondent for The Economist and director of The Future Africa Afrotech Initiative, who currently lives in Africa? Or Nnedi Okorafor, who was born in Cincinatti to Igbo parents and maintains close ties to Nigeria? While such questions have no straightforward answers, there is much to be gained by thinking collectively about them. My own instinct is not to try to nail down a rigid schema, but to keep matters fluid, relationships open, and potentials in play, and to recognize the specific conjunctural value of “African sf” as a temporary, flexible, non-monolithic, and, above all, strategic identity.

All of the stories and novels discussed below were either written or have been translated into English. There are undoubtedly works in indigenous languages, as well as in Arabic2 and other European colonizer languages. In terms of which texts are in print, a course on African sf would have to focus on fiction from after the post-World War 2 independence struggles, with the possibility of shifting emphasis from “literary” to “popular” fiction the closer it draws to the present; it is difficult to imagine an sf course that would contain so many Nobel laureates and so much experimental prose, while at the same time requiring students to find the value in pulp. Such a course would probably be suitable only for upper level undergraduates or postgraduates, which indicates the importance of incorporating African sf into general courses on sf, African literature, children’s and YA fiction, and so on.

I have noted whether pre-1980 out-of-print texts are held by the British Library (BL), Library of Congress (LC), the Eaton Collection at UC Riverside (E), the Merril collection at Toronto Public Library (M), or the Foundation collection at Liverpool University (F); post-1980 texts are much easier to find second-hand.

Was there African sf before World War 2?

All the examples I have found are by white South Africans, and only one of them (Timlin) is currently in print.

Joseph J. Doke’s The Secret City: A Romance of the Karroo (1913; BL, E) is a Haggard-inspired lost race novel, written by the Johannesburg-based Baptist clergyman who also wrote the authorized biography of Gandhi. In the frame tale, Justin Retief, a Cape Town settler, discovers a manuscript describing the adventures of his grandfather two centuries earlier. In the framed tale, Paul Retief witnesses the destruction of the millennia-old Nefert, a forgotten outpost of the ancient Egyptian empire, while rescuing his abducted wife, Marion, believed to be a reincarnation of the legendarily cruel queen Reinhild. The prequel, The Queen of the Secret City (1916; BL, E), tells of the rise to power (and the struggle over the soul) of Reinhild – again taken from a manuscript discovered by Justin. It is positioned as an overtly Christian refutation of pernicious Nietzscheanism, but rather clumsily, as if an afterthought. Both books are rare and costly.

Archibald Lamont’s South Africa in Mars (1923; BL, LC) is a posthumous account of encounters with the deceased great and good – including Shakespeare and Cecil Rhodes – on Mars, and involves a supernatural interplanetary scheme to save South Africa from its own failings. The brief description in Everett Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Early Years (1990) astutely “wonders why the book was written” (418). It is not too expensive second-hand.

British-born William M. Timlin emigrated to South Africa in 1912, aged twenty, where he became an architect and, more notably, an interior designer of picture palaces. His only novel, The Ship that Sailed to Mars (1923), is considered one of the most beautiful children’s books of the period – and one of the rarest. 2000 copies were published in London, priced at five guineas (250 of them were exported to the US, and sold for twelve dollars each). In 1926, Paramount announced a film adaptation, to star the now largely forgotten Raymond Griffith, but it went unmade, and the book was not reprinted until 2011. It contains 48 pages of text – not typeset but replicating Timlin’s calligraphy – and 48 paintings, telling the story of how fairies help the Old Man build a ship to travel, in a roundabout way, to the red planet, and of the fantastical civilization he finds there. Timlin’s whimsical blend of sf and fantasy recalls the films of Georges Méliès, perhaps, or Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo, though without the latter’s manic energy or sometimes sharp bite; visually, it is much closer to Arthur Rackham.

British-born William M. Timlin emigrated to South Africa in 1912, aged twenty, where he became an architect and, more notably, an interior designer of picture palaces. His only novel, The Ship that Sailed to Mars (1923), is considered one of the most beautiful children’s books of the period – and one of the rarest. 2000 copies were published in London, priced at five guineas (250 of them were exported to the US, and sold for twelve dollars each). In 1926, Paramount announced a film adaptation, to star the now largely forgotten Raymond Griffith, but it went unmade, and the book was not reprinted until 2011. It contains 48 pages of text – not typeset but replicating Timlin’s calligraphy – and 48 paintings, telling the story of how fairies help the Old Man build a ship to travel, in a roundabout way, to the red planet, and of the fantastical civilization he finds there. Timlin’s whimsical blend of sf and fantasy recalls the films of Georges Méliès, perhaps, or Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo, though without the latter’s manic energy or sometimes sharp bite; visually, it is much closer to Arthur Rackham.

Leonard Flemming, a farmer and occasional journalist, included the brief story ‘And So It Came to Pass’ in A Crop of Chaff (1925 BL), a collection of slight vignettes and humorous pieces. It is slight, but not remotely humorous. After whites have been eradicated, black people and coloured people turn on each other, destroying the human race.

Another early South African sf novel, published just after WW2 is When Smuts Goes: A History of South Africa from 1952 to 2010, first published in 2015 (1947; BL, LC, E, M) by Arthur Keppel-Jones, a professor of History at Witwatersrand University. Intended as an intervention into post-war South African politics, it projects a future in which Anglophone government is overthrown and replaced by a fascist Afrikaner state. The white Anglophone population deserts, or is hounded out of, the country. Black Africans eventually achieve a rather compromised victory over their oppressors, but prove incapable of building or maintaining a modern, thriving nation. Overall, it is one of those oddly racist anti-racist books, reiterating that old nonsense about British colonialism being more benevolent and efficient than that of other European nations. Nonetheless, it is worth the effort of finding one of the reasonably-priced second-hand copies.

Another early South African sf novel, published just after WW2 is When Smuts Goes: A History of South Africa from 1952 to 2010, first published in 2015 (1947; BL, LC, E, M) by Arthur Keppel-Jones, a professor of History at Witwatersrand University. Intended as an intervention into post-war South African politics, it projects a future in which Anglophone government is overthrown and replaced by a fascist Afrikaner state. The white Anglophone population deserts, or is hounded out of, the country. Black Africans eventually achieve a rather compromised victory over their oppressors, but prove incapable of building or maintaining a modern, thriving nation. Overall, it is one of those oddly racist anti-racist books, reiterating that old nonsense about British colonialism being more benevolent and efficient than that of other European nations. Nonetheless, it is worth the effort of finding one of the reasonably-priced second-hand copies.

First encounters

For a class on African sf, a provocative opening exercise – I am entirely indebted to Isiah Lavender III for this idea – would be to read Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) alongside Nigerian Chinua Achebe’s debut novel, Things Fall Apart (1958). Although neither is sf, both do science-fictional things. Conrad’s novel is somewhat reflexive about the colonial adventure fiction of the period, but remains deeply problematic in its depiction of Africa and Africans (as Achebe’s devastating critique in his 1975 lecture “An Image of Africa” (1978) persuasively demonstrated, single-handedly changing the way the novel is understood). Conrad depicts the journey into Africa as also one into a prehistoric past, transforming a common colonial trope of travelling backwards along the path of progress into something more akin to Verne’s A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864). The abandoned relics of previous colonial incursions into the continent suggest there is nothing inevitable about “progress,” while also echoing the “last man” tradition of a traveler finding Europe in ruins. The recurring sound of distant blasting and especially the image of a French battleship blindly shelling the jungle indicate the violence of colonial conquest and render modernity absurd. And if we can now also see the sf structures and moments in Conrad’s tale, Achebe’s novel – which is set in a fictional Igbo village in the late nineteenth century, and tells of the coming of white people, Christianity, and colonial governance – can also be read as a science-fictional account of first contact but from the other side.

Ideally, I would add Nigerian Buchi Emecheta’s The Rape of Shavi (1983) into this mix. Told primarily from the viewpoint of the inhabitants of Shavi, an isolated African kingdom, it depicts the arrival of a group of albinos in a “bird of fire” – in fact, westerners fleeing what they fear is a nuclear war – and of the various, increasingly tragic, misunderstandings as both peoples see the other through their own cultural standards and preconceptions. Perhaps inevitably, colonialism wins; the Shavians certainly do not. However, as the novel is out of print, an alternative elaboration on this exercise might be to introduce two of the very best stories about colonial encounters American sf has produced, Sonya Dorman’s “When I Was Miss Dow” (1968) and Octavia Butler’s “Bloodchild” (1984), which draw out in more overtly science-fictional ways some elements of colonial ideology – especially around gender, sexuality, reproduction, cooptation, and cooperation – that are central to neither Conrad nor Achebe.

Ideally, I would add Nigerian Buchi Emecheta’s The Rape of Shavi (1983) into this mix. Told primarily from the viewpoint of the inhabitants of Shavi, an isolated African kingdom, it depicts the arrival of a group of albinos in a “bird of fire” – in fact, westerners fleeing what they fear is a nuclear war – and of the various, increasingly tragic, misunderstandings as both peoples see the other through their own cultural standards and preconceptions. Perhaps inevitably, colonialism wins; the Shavians certainly do not. However, as the novel is out of print, an alternative elaboration on this exercise might be to introduce two of the very best stories about colonial encounters American sf has produced, Sonya Dorman’s “When I Was Miss Dow” (1968) and Octavia Butler’s “Bloodchild” (1984), which draw out in more overtly science-fictional ways some elements of colonial ideology – especially around gender, sexuality, reproduction, cooptation, and cooperation – that are central to neither Conrad nor Achebe.

Irreal Africas, postcolonial fictions

One place to look for traces of African sf is in critical volumes which would never dream of using the term, or would at least prefer not to, deploying instead a de-science-fictionalized discourse of utopia and dystopia, and labelling anything irreal as some kind of postcolonial magic realism or avant-gardist experimentalism. Gerald Gaylard’s After Colonialism: African Postmodernism and Magical Realism (2005) is a treasure trove in this regard. Without Gaylard, for example, I might never have come across South African Ivan Vladislavić’s satirical, often Kafkaesque short stories collected in Missing Persons (1989) and Propaganda by Monuments (1996), many of which – for example, “The Omniscope (Pat. Pending),” “We Came to the Monument,” and “A Science of Fragments” – contain sf elements. (Both volumes are out of print, and second-hand copies of Flashback Hotel (2010), the omnibus edition intended to make these stories accessible once more, are even harder to track down.)

Who Remembers the Sea (1962; BL in French, LC) – written by Algerian Mohammed Dib while exiled in Paris for his opposition to the French colonial occupation of Algeria – is set in a phantasmagorical city that constantly shifts and changes. Strange beasts roam the city, and violent conflict brings death and devastation. Apart from several more or less straightforwardly realistic flashbacks to the narrator’s youth, the novel is told in an elusive manner. It is replete with neologisms and neosemes, used with the consistency one would expect of sf world-building, even if the objects to which they attach are not brought into clear focus. Events and entities never quite seem to hold still. The revolution, if that is what it is, happens offstage, just out of sight. Each chapter seems to have forgotten the preceding one, and sometimes this is the case with paragraphs, too. It is a remarkable account of living under occupation.

Who Remembers the Sea (1962; BL in French, LC) – written by Algerian Mohammed Dib while exiled in Paris for his opposition to the French colonial occupation of Algeria – is set in a phantasmagorical city that constantly shifts and changes. Strange beasts roam the city, and violent conflict brings death and devastation. Apart from several more or less straightforwardly realistic flashbacks to the narrator’s youth, the novel is told in an elusive manner. It is replete with neologisms and neosemes, used with the consistency one would expect of sf world-building, even if the objects to which they attach are not brought into clear focus. Events and entities never quite seem to hold still. The revolution, if that is what it is, happens offstage, just out of sight. Each chapter seems to have forgotten the preceding one, and sometimes this is the case with paragraphs, too. It is a remarkable account of living under occupation.

In the Egyptian Moustafa Mahmoud’s slender The Rising from the Coffin (1965; LC), an Egyptian archeologist visits Indian Brahma Wagiswara, and then timeslips (or perhaps merely dreams) his way back to the era of the Pharaohs, in which Imhotep seems also to be Wagiswara. Scientific and spiritual worldviews are brought into collision, only for the narrator/protagonist to learn that they are not necessarily contradictory. Mahmoud’s The Spider (1965) was translated and serialized (1965–66) in Arab Observer, but I have been unable to locate any copies.

The Ghanaian [B.] Kojo Laing writes complex, experimental confections using sf, fantasy, and realist elements. Woman of the Aeroplanes (1988) brings two immortal communities – Tukwan, a fantastical community in Ghana, and Levensvale, a disentimed Scottish village – into complex contact with each other. Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars (1992) is discussed below. Big Bishop Roko and the Altar Gangsters (2006) is his largest, most sprawling, and most difficult novel to summarize, but it does involve, among many other sf elements, genetic engineering that makes it increasingly difficult for rich and poor countries to interact. Nigerian Ben Okri’s even more massive The Famished Road (1991) is easy reading in contrast. In a ghetto of an unnamed African city, the abiku (spirit-child) Azaro is constantly pressed by sibling spirits to return to their realm. In this often oneiric blend, sf imagery recurs.

The Ghanaian [B.] Kojo Laing writes complex, experimental confections using sf, fantasy, and realist elements. Woman of the Aeroplanes (1988) brings two immortal communities – Tukwan, a fantastical community in Ghana, and Levensvale, a disentimed Scottish village – into complex contact with each other. Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars (1992) is discussed below. Big Bishop Roko and the Altar Gangsters (2006) is his largest, most sprawling, and most difficult novel to summarize, but it does involve, among many other sf elements, genetic engineering that makes it increasingly difficult for rich and poor countries to interact. Nigerian Ben Okri’s even more massive The Famished Road (1991) is easy reading in contrast. In a ghetto of an unnamed African city, the abiku (spirit-child) Azaro is constantly pressed by sibling spirits to return to their realm. In this often oneiric blend, sf imagery recurs.

The novels I would choose to teach, though, are Congolese Sony Labou Tansi’s Life and A Half (1977) and Kenyan Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Wizard of the Crow (2006).

The former, set in the fictional republic of Katamalanasia, tells of resistance to a murderous dictator called The Providential Guide, and of the numerous, equally deadly and deranged offspring who compete to replace him. It culminates in an apocalyptic war that involves such superscience weapons as mutant flies whose sting turns their victims into radiant carbon, radio-flies with beam weapons, the radio-bomb, and the real rifle of peace. It is brief, hyperbolic, brutal, and comic.

The former, set in the fictional republic of Katamalanasia, tells of resistance to a murderous dictator called The Providential Guide, and of the numerous, equally deadly and deranged offspring who compete to replace him. It culminates in an apocalyptic war that involves such superscience weapons as mutant flies whose sting turns their victims into radiant carbon, radio-flies with beam weapons, the radio-bomb, and the real rifle of peace. It is brief, hyperbolic, brutal, and comic.

Thiong’o’s novel, set in the fictional state of Abruria, is much more accessible, but much more massive. An irreal burlesque, indignant at the state of postcolonial Africa, it excoriates brutal domestic corruption and its interrelations with a global economic system constructed to serve the interests of the former and neo-colonialists. For example, in one strand, a government minister jockeying for position plans to build the tallest building in the world – so tall, in fact, that Abruria must develop a space program in order to take the President, by rocket, to its penthouse.

Thiong’o’s novel, set in the fictional state of Abruria, is much more accessible, but much more massive. An irreal burlesque, indignant at the state of postcolonial Africa, it excoriates brutal domestic corruption and its interrelations with a global economic system constructed to serve the interests of the former and neo-colonialists. For example, in one strand, a government minister jockeying for position plans to build the tallest building in the world – so tall, in fact, that Abruria must develop a space program in order to take the President, by rocket, to its penthouse.

An alternative for those daunted by the sheer size of Wizard of the Crow might be Ivorian Ahmadou Kourouma’s Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote (1998), which recounts the life of a shapeshifting dictator and the history of African decolonization/neo-colonization. Utterly fantastical and in some ways completely true, it is shorter yet more grueling than Wizard, but lacks Thiong’o’s humour and overt sf elements.

An alternative for those daunted by the sheer size of Wizard of the Crow might be Ivorian Ahmadou Kourouma’s Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote (1998), which recounts the life of a shapeshifting dictator and the history of African decolonization/neo-colonization. Utterly fantastical and in some ways completely true, it is shorter yet more grueling than Wizard, but lacks Thiong’o’s humour and overt sf elements.

Pulp Africas, cyberpunk Africas

There are a number of African texts which we can think of as being closely related to western pulp traditions. Ghanaian Victor Sabah’s brief, self-consciously naïve ‘An Imaginary Journey to the Moon’ (1972) was collected in Harry Harrison and Brian Aldiss’s variously titled Best SF: 1972 (1973) and again in Aldiss and Sam Lundwall’s The Penguin World Omnibus of Science Fiction (1986), although editors seems reluctant to detail where it first appeared. South African Claude Nunes – sometimes with Rhoda Nunes as co-author – published a couple of short stories, ‘The Problem’ (1962) and ‘Inherit the Earth’ (1963) in, respectively, John Carnell’s Science Fantasy and Science Fiction Adventures magazines in the UK, before seeing a pair of short novels, Inherit the Earth (1967) and Recoil (1971), as halves of Ace Doubles in the US. The Sky Trapeze (1980) was published in the UK. All three novels are available on kindle. They are competent enough, and their depiction of struggles between humans and posthumans of various sorts could be seen as commenting on Apartheid. However, they are so grounded in American sf – apocalyptic wars, androids, mutants, psi powers, group minds, interstellar travel – that their occasional African settings and traces of a South African perspective are rather overwhelmed.

The Apex Book of World SF 2 (2012) and 3 (2014), edited by Lavie Tidhar, include stories from Gambia, Malawi, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Ivor Hartmann’s AfroSf: Science Fiction by African Writers anthology (2012) contains 22 new short stories from across the continent (including Gambia, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and, primarily, South Africa). This groundbreaking collection displays various, often quite complex, interrelations between African content, settings, and culture, and US pulp traditions, protocols, and story types. A sequel volume of novellas is forthcoming.

The Apex Book of World SF 2 (2012) and 3 (2014), edited by Lavie Tidhar, include stories from Gambia, Malawi, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Ivor Hartmann’s AfroSf: Science Fiction by African Writers anthology (2012) contains 22 new short stories from across the continent (including Gambia, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and, primarily, South Africa). This groundbreaking collection displays various, often quite complex, interrelations between African content, settings, and culture, and US pulp traditions, protocols, and story types. A sequel volume of novellas is forthcoming.

There are also a number of thrillers with significant sf elements. The popular and prolific Kenyan David G. Maillu, winner of the 1992 Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature, wrote several sf novels. The Equatorial Assignment (1980) introduces special agent 009, Benni Kamba. He works for the covert pan-Africanist security organization NISA (National Integrity Service of Africa) in the struggle against neo-colonial power, here represented by Dr Thunder’s SPECTRE-like operation, which is engaged in removing any remotely effective African head of state and replacing him with a puppet ruler. The influence of the James Bond films (rather than Ian Fleming’s novels) on this slight and rather crudely written YA novel is clear. Every woman 009 meets is beautiful and sooner or later ends up in bed with him, though only one of them subsequently betrays him (but her confused feelings for him then lead to a moment of weakness which enables him to triumph). Operation DXT (1986) is a sequel, while Kadosa (1975; BL) is an sf romance, in which the eponymous alien woman visits contemporary

There are also a number of thrillers with significant sf elements. The popular and prolific Kenyan David G. Maillu, winner of the 1992 Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature, wrote several sf novels. The Equatorial Assignment (1980) introduces special agent 009, Benni Kamba. He works for the covert pan-Africanist security organization NISA (National Integrity Service of Africa) in the struggle against neo-colonial power, here represented by Dr Thunder’s SPECTRE-like operation, which is engaged in removing any remotely effective African head of state and replacing him with a puppet ruler. The influence of the James Bond films (rather than Ian Fleming’s novels) on this slight and rather crudely written YA novel is clear. Every woman 009 meets is beautiful and sooner or later ends up in bed with him, though only one of them subsequently betrays him (but her confused feelings for him then lead to a moment of weakness which enables him to triumph). Operation DXT (1986) is a sequel, while Kadosa (1975; BL) is an sf romance, in which the eponymous alien woman visits contemporary  Kenya. Nigerian Valentine Alily’s Mark of the Cobra (1980) is another Bond-inspired short YA novel: Ca’afra Osiri Ba’ara, aka the Cobra, has developed a devastating solar weapon, and only Nigeria’s Special Service Agent, SSA2 Jack Ebony, can thwart his plans for global domination. The villain even acknowledges when he is quoting from Live and Let Die. A Beast in View (1969 BL, F), by anti-apartheid South African exile Peter Dreyer, was banned in South Africa on publication. In this rather more literary near-future thriller, the League of South African Democrats uncover a scheme to frack oil from shale by detonating a nuclear bomb in the Karoo region.

Kenya. Nigerian Valentine Alily’s Mark of the Cobra (1980) is another Bond-inspired short YA novel: Ca’afra Osiri Ba’ara, aka the Cobra, has developed a devastating solar weapon, and only Nigeria’s Special Service Agent, SSA2 Jack Ebony, can thwart his plans for global domination. The villain even acknowledges when he is quoting from Live and Let Die. A Beast in View (1969 BL, F), by anti-apartheid South African exile Peter Dreyer, was banned in South Africa on publication. In this rather more literary near-future thriller, the League of South African Democrats uncover a scheme to frack oil from shale by detonating a nuclear bomb in the Karoo region.

However, probably the best route into thinking about African sf in relation to western pulp sf is through cyberpunk.3 South African Lauren Beukes’ first two novels, Moxyland (2008) and the Clarke Award-winner Zoo City (2010) are both cyberpunk-ish – the earlier more obviously so, but I would recommend teaching the stronger, later novel, which might also be considered as urban fantasy, not least since the best critical work on Beukes also focuses on Zoo City.4

However, probably the best route into thinking about African sf in relation to western pulp sf is through cyberpunk.3 South African Lauren Beukes’ first two novels, Moxyland (2008) and the Clarke Award-winner Zoo City (2010) are both cyberpunk-ish – the earlier more obviously so, but I would recommend teaching the stronger, later novel, which might also be considered as urban fantasy, not least since the best critical work on Beukes also focuses on Zoo City.4

A brilliant, and rather more challenging, companion novel is Ghanaian [B.] Kojo Laing’s experimental Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars (1992), whose phantasmagorical tale has a cyberpunkish setting. Set in 2020, it tells of the war between Major Gentl and the mercenary Torro the Terrible, with the fate of Achimoto City and perhaps all Africa hanging in the balance. It is dense, fantastical, poetic – and, I have just discovered, no longer in print.

A brilliant, and rather more challenging, companion novel is Ghanaian [B.] Kojo Laing’s experimental Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars (1992), whose phantasmagorical tale has a cyberpunkish setting. Set in 2020, it tells of the war between Major Gentl and the mercenary Torro the Terrible, with the fate of Achimoto City and perhaps all Africa hanging in the balance. It is dense, fantastical, poetic – and, I have just discovered, no longer in print.

Perhaps, then, the Egyptian Ahmed Khaled Towfik’s Utopia (2008), often considered proleptic of the Arab Spring, might do instead. Cyberpunk elements lurk in the background of a world divided between the walled enclaves of the rich and the masses of impoverished and disenfranchised peoples living in the ruins. A young man from the former ventures into the latter for kicks, runs into trouble, returns, but doesn’t really learn anything. Or maybe Efe Okogu’s novella ‘Prop 23’ in AfroSF, which reworks elements of Neuromancer and biopolitical perspectives in a future Lagos.

Perhaps, then, the Egyptian Ahmed Khaled Towfik’s Utopia (2008), often considered proleptic of the Arab Spring, might do instead. Cyberpunk elements lurk in the background of a world divided between the walled enclaves of the rich and the masses of impoverished and disenfranchised peoples living in the ruins. A young man from the former ventures into the latter for kicks, runs into trouble, returns, but doesn’t really learn anything. Or maybe Efe Okogu’s novella ‘Prop 23’ in AfroSF, which reworks elements of Neuromancer and biopolitical perspectives in a future Lagos.

Or, from among Afrodiasporic texts, The African Origins of UFOs (2006), the afro-psychedelic noir sf novel by British-Trinidadian poet and musician Anthony Joseph (his reading of extracts on the 2005 Liquid Textology CD is also highly recommended). Or perhaps Parisian-born Tunisian Nadia El Fani’s film Bedwin Hacker (France/Morocco/Tunisia 2003), a low-key political thriller about neo-colonial power relations in which a French Intelligence agent tries to track down a North African hacker. It is available on DVD – whereas Cameroonian Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s Les Saignantes/The Bloodiest (Cameroon 2005), which plays with cyberpunk imagery in much more challenging ways, is not.

Or, from among Afrodiasporic texts, The African Origins of UFOs (2006), the afro-psychedelic noir sf novel by British-Trinidadian poet and musician Anthony Joseph (his reading of extracts on the 2005 Liquid Textology CD is also highly recommended). Or perhaps Parisian-born Tunisian Nadia El Fani’s film Bedwin Hacker (France/Morocco/Tunisia 2003), a low-key political thriller about neo-colonial power relations in which a French Intelligence agent tries to track down a North African hacker. It is available on DVD – whereas Cameroonian Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s Les Saignantes/The Bloodiest (Cameroon 2005), which plays with cyberpunk imagery in much more challenging ways, is not.

YA fiction

I have not read Ghanaian J.O. Eshun’s The Adventures of Kapapa (1976; F), about a scientist who discovers antigravity, nor have I been able to find a copy of Journey to Space (1980),5 a novella by Nigerian Flora Nwapa, who is widely regarded as “the mother of modern African literature.”

The Arizonan writer Nancy Farmer spent 17 years living and working in Africa – South Africa, Mozambique, mostly Zimbabwe – where she started to publish fiction. After winning the 1987 Writers of the Future gold award, she returned to the US. Her debut novel, The Ear, The Eye and The Arm was published in Zimbabwe in 1989; the much-revised 1994 version won numerous awards.6 Set in 2194, it tells of the abduction of General Matsika’s children, of their adventures in Harare’s various communities, and of the search for them by the three hapless, mutant detectives of the title.

The Arizonan writer Nancy Farmer spent 17 years living and working in Africa – South Africa, Mozambique, mostly Zimbabwe – where she started to publish fiction. After winning the 1987 Writers of the Future gold award, she returned to the US. Her debut novel, The Ear, The Eye and The Arm was published in Zimbabwe in 1989; the much-revised 1994 version won numerous awards.6 Set in 2194, it tells of the abduction of General Matsika’s children, of their adventures in Harare’s various communities, and of the search for them by the three hapless, mutant detectives of the title.

It is tempting to select Nigerian-American Nnedi Okorafor’s Zahrah the Windseeker (2005), The Shadow Speaker (2007) or Akata Witch (2011) as the YA novels to teach; they are highly-regarded and easily available, and they nicely trouble distinctions between sf and fantasy. However, a course on African SF might be better served by her adult novels, and by instead looking at YA sf from other writers: Zambian-born naturalized South African Nick Wood’s The Stone Chameleon (2004) and Botswana-resident South African Jenny Robson’s Savannah 2116 AD (2004). The former is a relatively slight adventure novel in a post truth-and-reconciliation South Africa of 2030. Race is no longer an issue, apart from all the ways it continues to be one. Kerem, the fifteen-year-old protagonist, and a handful of friends from his new school, find themselves standing up to a neighborhood criminal gang – complete with heavies genetically altered to incorporate physical traits of wild animals – and questing for an ancient source of power that will heal the African communities desolated and divided by European colonialism and its long aftermath. Robson’s novel, aimed at older readers, is a little longer, more complex and more accomplished. It imagines a 22nd-century Africa in which the majority of humans – called, dismissively, “Homosaps” – live on reservations so as to enable the continent’s flora and fauna to recover from global anthropogenic ecocatastrophe. The teenage Savannah, and her new boyfriend, D-nineteen, who is one of the mysterious “gens” – that is, he has been genetically engineered so that, at the age of eighteen, his organs can be harvested and, ostensibly, transplanted into struggling animals – discover all is not as it seems. Both novels are also susceptible to readings from animal studies and biopolitical perspectives.

It is tempting to select Nigerian-American Nnedi Okorafor’s Zahrah the Windseeker (2005), The Shadow Speaker (2007) or Akata Witch (2011) as the YA novels to teach; they are highly-regarded and easily available, and they nicely trouble distinctions between sf and fantasy. However, a course on African SF might be better served by her adult novels, and by instead looking at YA sf from other writers: Zambian-born naturalized South African Nick Wood’s The Stone Chameleon (2004) and Botswana-resident South African Jenny Robson’s Savannah 2116 AD (2004). The former is a relatively slight adventure novel in a post truth-and-reconciliation South Africa of 2030. Race is no longer an issue, apart from all the ways it continues to be one. Kerem, the fifteen-year-old protagonist, and a handful of friends from his new school, find themselves standing up to a neighborhood criminal gang – complete with heavies genetically altered to incorporate physical traits of wild animals – and questing for an ancient source of power that will heal the African communities desolated and divided by European colonialism and its long aftermath. Robson’s novel, aimed at older readers, is a little longer, more complex and more accomplished. It imagines a 22nd-century Africa in which the majority of humans – called, dismissively, “Homosaps” – live on reservations so as to enable the continent’s flora and fauna to recover from global anthropogenic ecocatastrophe. The teenage Savannah, and her new boyfriend, D-nineteen, who is one of the mysterious “gens” – that is, he has been genetically engineered so that, at the age of eighteen, his organs can be harvested and, ostensibly, transplanted into struggling animals – discover all is not as it seems. Both novels are also susceptible to readings from animal studies and biopolitical perspectives.

The borderlines of sf

In Africa, as elsewhere, fiction often lurks right on the edges of the genre. For example, The Last of the Empire (1981) by Senegalese Ousmane Sembene – not only a leading African novelist but also “the father of African Cinema” – is a political thriller about a military coup in a newly independent African nation; it is also almost a roman à clef about Senegal, satirizing its first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, with whom Sembene often butted heads. This hesitancy about the nature of the novel’s setting gives it an oddly science-fictional air. A similar science-fictionality haunts the Zimbabwean Dambudzo Marechera’s The Black Insider (written 1978, posthumously published 1990), in which autobiographical reminiscences are told from within a derelict university building outside of which a war rages. The non-specific location of J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians (1980), which takes place in a frontier settlement as war between the Empire and the barbarians looms, draws it even closer to sf.7 In contrast, South African Nadine Gordimer’s July’s People (1981) is clearly set in the near-future, with resistance to Apartheid becoming open revolution. Despite this specificity, the novel feels perhaps less science-fictional than Waiting for the Barbarians since its focus is on the shifting relationship between a liberal white family and their black African servant who shelters them in his village, a remote home to which the pass system would only otherwise have permitted him to return every two years.

(1980), which takes place in a frontier settlement as war between the Empire and the barbarians looms, draws it even closer to sf.7 In contrast, South African Nadine Gordimer’s July’s People (1981) is clearly set in the near-future, with resistance to Apartheid becoming open revolution. Despite this specificity, the novel feels perhaps less science-fictional than Waiting for the Barbarians since its focus is on the shifting relationship between a liberal white family and their black African servant who shelters them in his village, a remote home to which the pass system would only otherwise have permitted him to return every two years.

J.M. Ledgard’s Submergence (2012) juxtaposes the lives of James and Danny before and especially after they meet one Christmas and fall in love: a British spy, and a descendant of Thomas More, he is abducted by jihadists in Somalia; a biomathematician, she studies microbial life in the Hadal depths of the Atlantic ocean. Occasionally too precious for its own good (it is the kind of novel in which one character will quote Rilke in German to the other), it establishes a series of genuinely effective contrasts between the immediacy of James’s experience and the sublime spaces and times of Danny’s.

I would, however, select a couple of debut novels to probe our understanding of the relationships between genres, the ways in which texts are comprised of multiple generic elements and tendencies – and to question the process of using Anglo-American categories to consider African novels.

Nigerian Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come to You By Chance (2009) won a Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, a Wole Soyinka Prize, and a Betty Trask Award.8 It is a fast-paced comedy of desperation in which the well-educated Kingsley lacks the right connections to get a job as an engineer. When his father falls ill, and essential medical treatment proves too costly, Kingsley – now also responsible, as the opara (first-born son), for the wellbeing of his whole family – finds himself propelled into the world of 419 scammers. If it had been written by William Gibson or Neal Stephenson, no-one would think twice about treating it as sf.

Nigerian Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come to You By Chance (2009) won a Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, a Wole Soyinka Prize, and a Betty Trask Award.8 It is a fast-paced comedy of desperation in which the well-educated Kingsley lacks the right connections to get a job as an engineer. When his father falls ill, and essential medical treatment proves too costly, Kingsley – now also responsible, as the opara (first-born son), for the wellbeing of his whole family – finds himself propelled into the world of 419 scammers. If it had been written by William Gibson or Neal Stephenson, no-one would think twice about treating it as sf.

Nii Ayikwei Parkes was born in the UK and raised in Ghana. In The Tail of the Blue Bird (2009), Kayo – who trained in the UK as a forensic pathologist and worked as a police Scenes of Crime Officer – returns to Accra, hoping to pursue similar work. The Ghanaian police are uninterested in hiring him until the girlfriend of a government minister discovers baffling remains – they might be human, or not – in a distant village. Caught up in the potentially fatal machinations of an ambitious police officer and the webs of everyday urban violence and corruption, Kayo finds a rather different kind of community, with a deep history and traditional wisdom. The novel never quite becomes sf, and its treatment of forensic science refuses the absurd certainties of CSI, but fantastical elements emerge.

Nii Ayikwei Parkes was born in the UK and raised in Ghana. In The Tail of the Blue Bird (2009), Kayo – who trained in the UK as a forensic pathologist and worked as a police Scenes of Crime Officer – returns to Accra, hoping to pursue similar work. The Ghanaian police are uninterested in hiring him until the girlfriend of a government minister discovers baffling remains – they might be human, or not – in a distant village. Caught up in the potentially fatal machinations of an ambitious police officer and the webs of everyday urban violence and corruption, Kayo finds a rather different kind of community, with a deep history and traditional wisdom. The novel never quite becomes sf, and its treatment of forensic science refuses the absurd certainties of CSI, but fantastical elements emerge.

Alternative and future Africas

All of the books in this section would work well on an African sf course – and since I do not actually have to choose between them, I will not.

French-resident Djiboutian Abdourahman A. Waberi describes an alternate world In the United States of Africa (2006), in which Africa is the global superpower and Europe a mass of uncivilized tribes constantly fighting each other. This kaleidoscopic novel is not an alternative history as sf normally understands it – there is no jonbar point of historical divergence, nor is it entirely clear whether pre-colonial African civilizations just continued on in to the present. Furthermore, its descriptions of European internecine strife are not an inaccurate description of the continent’s actual history – Waberi merely refuses to drape it in the self-serving narratives of civilization and progress, instead imposing upon it the kind of supremacist myths that typify many European treatments of Africa. Malaika, a French girl adopted by an African doctor when he was working on an aid mission in the benighted continent, returns as an adult to her birthplace in the hope of finding her mother and a clearer sense of her own confused identity. This is a dazzling book, sharp and funny, and there is no way a synopsis can do it justice.9

French-resident Djiboutian Abdourahman A. Waberi describes an alternate world In the United States of Africa (2006), in which Africa is the global superpower and Europe a mass of uncivilized tribes constantly fighting each other. This kaleidoscopic novel is not an alternative history as sf normally understands it – there is no jonbar point of historical divergence, nor is it entirely clear whether pre-colonial African civilizations just continued on in to the present. Furthermore, its descriptions of European internecine strife are not an inaccurate description of the continent’s actual history – Waberi merely refuses to drape it in the self-serving narratives of civilization and progress, instead imposing upon it the kind of supremacist myths that typify many European treatments of Africa. Malaika, a French girl adopted by an African doctor when he was working on an aid mission in the benighted continent, returns as an adult to her birthplace in the hope of finding her mother and a clearer sense of her own confused identity. This is a dazzling book, sharp and funny, and there is no way a synopsis can do it justice.9

The Nigerian-American Deji Bryce Olukotun’s Nigerians in Space (2013), largely written and much of it set in South Africa, is an intriguing thriller focused less on the neatly decentered scheme around which it is organized than on its aftermath. In the early 1990s, a politician recruits top scientists from the Nigerian diaspora to return home as part of the “Brain Gain” intended to transform the country through high-tech innovation; in the present day, it transpires that only one of the scientists escaped assassination before the project – or was it just a scam? – could cohere.

The Nigerian-American Deji Bryce Olukotun’s Nigerians in Space (2013), largely written and much of it set in South Africa, is an intriguing thriller focused less on the neatly decentered scheme around which it is organized than on its aftermath. In the early 1990s, a politician recruits top scientists from the Nigerian diaspora to return home as part of the “Brain Gain” intended to transform the country through high-tech innovation; in the present day, it transpires that only one of the scientists escaped assassination before the project – or was it just a scam? – could cohere.

Nnedi Okorafor’s World Fantasy Award-winning Who Fears Death (2010) is set in a post-apocalyptic future in which technology and magic operate side by side, and in which dark-skinned Okeke are oppressed by light-skinned Nuru. Onyesonwu, the child of a Nuru woman raped by an Okeke sorcerer, learns to use her powers to prevent the genocide her father plans. Similarly structured to her YA novels, Who Fears Death is about rape, female genital mutilation, violation, trauma, the legacies of violence, the justifications for violence, ethnic struggles, gendered power, political and ethical responsibility, among other things, and wisely avoids proffering easy solutions.

Nnedi Okorafor’s World Fantasy Award-winning Who Fears Death (2010) is set in a post-apocalyptic future in which technology and magic operate side by side, and in which dark-skinned Okeke are oppressed by light-skinned Nuru. Onyesonwu, the child of a Nuru woman raped by an Okeke sorcerer, learns to use her powers to prevent the genocide her father plans. Similarly structured to her YA novels, Who Fears Death is about rape, female genital mutilation, violation, trauma, the legacies of violence, the justifications for violence, ethnic struggles, gendered power, political and ethical responsibility, among other things, and wisely avoids proffering easy solutions.

In Lagoon (2014), Okorafor leaves behind her YA structure for a fast-paced thriller, and offers a more optimistic vision of a future Africa – or, more precisely, a future Lagos. By her own account, she started the novel as a response to the infuriating District 9 (Blomkamp US/NZ/Canada/South Africa) but, as she wrote, it transformed into something else. Aliens land in the lagoon, bringing chaos – a gang wants to kidnap the aliens, evangelical Christians want to convert them, an underground LGBT group sees in them a harbinger of revolution, the government is too slow and corrupt to respond effectively – and transformation; and Nigeria for once appears in the global mediascape as something other than a source of oil and location of violence.10

In Lagoon (2014), Okorafor leaves behind her YA structure for a fast-paced thriller, and offers a more optimistic vision of a future Africa – or, more precisely, a future Lagos. By her own account, she started the novel as a response to the infuriating District 9 (Blomkamp US/NZ/Canada/South Africa) but, as she wrote, it transformed into something else. Aliens land in the lagoon, bringing chaos – a gang wants to kidnap the aliens, evangelical Christians want to convert them, an underground LGBT group sees in them a harbinger of revolution, the government is too slow and corrupt to respond effectively – and transformation; and Nigeria for once appears in the global mediascape as something other than a source of oil and location of violence.10

Lagos 2060 (2013) edited by Ayodele Arigbabu, collects eight stories developed out of a workshop in 2010, Nigeria’s golden anniversary year, concerned with imagining Lagos, already Africa’s most populous city, a century after the country’s independence. The stories contain different futures, though with some elements in common, and address global warming and other ecological concerns, nuclear disasters, the continuing role of foreign capital in determining the national economy and thus daily life, the nature of a post-oil Nigerian economy and state, the potential secession of Lagos and balkanization of the Federal State, the polarization of the wealthy and the impoverished, and developments such as the Eko Atlantic City as a moneyed enclave. They are quite pulpy and sometimes crudely written – further evidence of the need Tade Thompson described for regular paying markets for sf in Africa in order for writers to develop their craft – but they represent an important step in the development of African, and specifically Nigerian, sf.

Lagos 2060 (2013) edited by Ayodele Arigbabu, collects eight stories developed out of a workshop in 2010, Nigeria’s golden anniversary year, concerned with imagining Lagos, already Africa’s most populous city, a century after the country’s independence. The stories contain different futures, though with some elements in common, and address global warming and other ecological concerns, nuclear disasters, the continuing role of foreign capital in determining the national economy and thus daily life, the nature of a post-oil Nigerian economy and state, the potential secession of Lagos and balkanization of the Federal State, the polarization of the wealthy and the impoverished, and developments such as the Eko Atlantic City as a moneyed enclave. They are quite pulpy and sometimes crudely written – further evidence of the need Tade Thompson described for regular paying markets for sf in Africa in order for writers to develop their craft – but they represent an important step in the development of African, and specifically Nigerian, sf.

African sf is already at least a century old. It is – as I hope this undoubtedly incomplete overview suggests – wonderfully diverse and increasingly common. It challenges us to rethink our understanding of the genre, and how we think about the past, the present, and the future. It deserves – indeed, demands – our attention. Not as a poor relative in need of charity, but as an equal from whom we all have much to learn.

[There is an update here.]

Notes

1

It has been argued, for example, that the European success of Sony Labou Tansi’s debut novel, Life and a Half (1979), was indebted in large part to its misidentification as “magic realist,” a categorisation that produces significant misunderstandings of both the novel and Congolese culture (labelling it as sf shifts how it can be understood but of course invites exactly the same criticism). At “Imagining Future Africa: SciFi, Innovation and Technology,” the closing panel at the third annual Africa Writes festival at the British Library (11-13 July 2014), British-Nigerian Tade Thompson raised a related problem: without regular, paying markets in Africa for sf of African origin, African writers are likely to orient their fiction towards US or European markets rather than pursue more indigenous forms and concerns. (December 2014 saw the launch of Omenana, a free bimonthly online magazine of African and Afrodiasporic sf, edited by Mazi Nwonwu and Chinelo Onwualu; and January 2105 saw the launch of Jalada’s online Afrofutures anthology.)

2

For example, the SFE’s “Arabic sf” entry refers to untranslated sf by the Egyptians Tawfiq al Hakim, Mustafa Mahmud, Yusuf Idris, and Ali Salim, the Libyan Yusuf al-Kuwayri, the Tunisian Izzaddin al-Madani, and the Algerian Hacène Farouk Zehar, who wrote in French (as did Algerian Mohammed Dib, whose sf novel I discuss in this essay). Some of Tawfiq al Hakim’s sf has been translated into English. His “In the Year One Million” (1947), depicts a sexless, immortal, future humanity rediscovering love, mortality, and religion; it is included in In the Tavern of Life and Other Stories (1998). Some of its themes are developed in his four-act play Voyage to Tomorrow (1957) and his one-act play Poet on the Moon (1972), both of which can be found in Plays, Prefaces and Postscripts of Tawfiq Al-Hakim, volume two: Theater of Society (1984). In the former, a doctor and an engineer, both facing execution, are offered reprieves if they will pilot an experimental rocket into the depths of space. After a fatal crash, they find themselves revived as immortal beings on an empty alien world, faced with the emptiness of eternity. They return to Earth, somehow human once more, and find that during their three-hundred-year absence, the world has become a utopia of peace and plenty – and that humanity faces a similarly meaningless future. In the latter play, a poet maneuvers his way onto a lunar expedition. He alone is able to perceive the alien inhabitants, living at peace since becoming sexless, and to recognize that his fellow astronaut’s discovery of the Moon’s mineral wealth can only result in colonial devastation.

3

Ghanaian Jonathan Dotse has been working on a cyberpunk novel, Accra: 2057, for several years, although it remains unclear how soon it will be completed.

4

Beukes’ subsequent novels, The Shining Girls (2013) and Broken Monsters (2014), combine serial killer thrillers with sf and fantastical elements. They are a useful reminder – as is Doris Lessing’s sf, which I have omitted from this outline since her work is already well known – that we should not expect African writers necessarily to set their fiction in Africa.

5

WorldCat notes copies are held by four German universities and by Northwestern in the US.

6

Her other sf includes the bleak, near-future diptych, The House of the Scorpion (2002) and The Lord of Opium (2013), set on the contested US-Mexico border. The Warm Place (1995), the Zimbabwe-set A Girl Named Disaster (1996), and the Sea of Trolls trilogy (2004-2009) are fantasy.

7

His In the Heart of the Country (1977) features a fleeting UFO appearance.

8

Nwaubani’s mother is a cousin of Flora Nwapa.

9

Africa Paradis (Sylvestre Amoussou Benin/France 2006) conjures a broader similar near future after the collapse of Europe, the newly-risen African superpower is plagued by the problem of illegal immigrants from Europe; it is available on DVD. Yet another version of this role-reversal milieu features in the final and longest film in Omer Fast’s Nostalgia (2006), a triptych shown as a gallery installation. It is more nuanced than Amoussou’s feature film, but pretty much unavailable unless you are near a gallery where it is showing. Even though both films would work well as accompaniments to Waberi’s novel neither of them is in its league.

10

A somewhat less compelling vision of apocalyptic transformation can be found in The Feller of Trees (2012), by Zambian Mwangala Bonna, who lives and works in South Africa and Botswana. In it, Berenice struggles to reconcile her Christian faith with the political machinations necessary to unite and save Africa when the continent begins to sink.

‘There’ is the Starbucks in Borders bookstore on Oxford Street, our default meeting-up place in central London, and we would leave ‘there’ as soon as possible, and grab some pizza at a place around the corner (where, a year earlier, our arrival had been greeted with rapturous applause from the staff – not because they recognised China, but because they’d been open for almost an hour and we were their first customers that day). And after lunch, although the pretext for meeting up was discussing essay proposals for a book we are editing on Marxism and sf, we would head to the Natural History Museum to see the thirty-foot long, newly-on-display, giant squid.

‘There’ is the Starbucks in Borders bookstore on Oxford Street, our default meeting-up place in central London, and we would leave ‘there’ as soon as possible, and grab some pizza at a place around the corner (where, a year earlier, our arrival had been greeted with rapturous applause from the staff – not because they recognised China, but because they’d been open for almost an hour and we were their first customers that day). And after lunch, although the pretext for meeting up was discussing essay proposals for a book we are editing on Marxism and sf, we would head to the Natural History Museum to see the thirty-foot long, newly-on-display, giant squid. ‘Trains,’ I tut, to boost my curmudgeon-score as we share a mezze and several varieties of bread. But we have been talking about trains a lot, lately. I have a crazy notion that there is a book to be written about trains and early cinema and time-travel (but very distinctly not about early railroad films or time-travel movies), and China’s voracious reading, especially the research for Iron Council (and for his review of Stefan Grabinski’s The Motion Demon), keeps throwing up gems. It’s like having a really good research assistant I don’t have to supervise or pay (although he has still not returned my copies of The Iron Horse, Once Upon a Time in the West and Emperor of the North Pole).

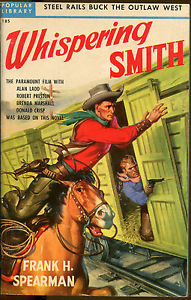

‘Trains,’ I tut, to boost my curmudgeon-score as we share a mezze and several varieties of bread. But we have been talking about trains a lot, lately. I have a crazy notion that there is a book to be written about trains and early cinema and time-travel (but very distinctly not about early railroad films or time-travel movies), and China’s voracious reading, especially the research for Iron Council (and for his review of Stefan Grabinski’s The Motion Demon), keeps throwing up gems. It’s like having a really good research assistant I don’t have to supervise or pay (although he has still not returned my copies of The Iron Horse, Once Upon a Time in the West and Emperor of the North Pole). ‘Iron Council riffed heavily on Frank Spearman’s Whispering Smith. Spearman was a sort-of libertarian, reportedly Ayn Rand’s favourite writer, did lots of stuff about rugged railwaymen. Whispering Smith is a troubleshooter for the railroad who is allowed to go anywhere and do more or less anything, including kill anyone necessary, to “fix problems”. It is an extremely perspicacious critique of rugged individualist/libertarian railroadism (as I’ve christened the ideology), because contrary to the “enlightened self-interest” of the Randists and half of Spearman’s own characters, the thrusting of the rails is only possible with a roving assassin – a man in a permanent state of Schmittian law-making exception! – bringing peace for capital-expansion at the end of a gun beyond the bounds of the rails. So the railroad relies for the always-spurious solidity of even its semiotic status to the right on an implicit awareness of beyond-railroad coercion of the most violent kind. Spearman, a cunning writer, recognises this and rather than attempt to conceal it, hides its in plain view.’

‘Iron Council riffed heavily on Frank Spearman’s Whispering Smith. Spearman was a sort-of libertarian, reportedly Ayn Rand’s favourite writer, did lots of stuff about rugged railwaymen. Whispering Smith is a troubleshooter for the railroad who is allowed to go anywhere and do more or less anything, including kill anyone necessary, to “fix problems”. It is an extremely perspicacious critique of rugged individualist/libertarian railroadism (as I’ve christened the ideology), because contrary to the “enlightened self-interest” of the Randists and half of Spearman’s own characters, the thrusting of the rails is only possible with a roving assassin – a man in a permanent state of Schmittian law-making exception! – bringing peace for capital-expansion at the end of a gun beyond the bounds of the rails. So the railroad relies for the always-spurious solidity of even its semiotic status to the right on an implicit awareness of beyond-railroad coercion of the most violent kind. Spearman, a cunning writer, recognises this and rather than attempt to conceal it, hides its in plain view.’ ‘And then there’s Bruno Schulz, using trains (in several different ways – history as both inside and outside the train itself, on the rails as well as in the corridors) to think about the alterity of history and alternate possibilities. I’m increasingly interested by the idea of the multi-track nature of railroads, let alone Grabinski’s sidings, as key to their importance. There’s this astonishing passage in his ‘The Age of Genius’ in The Sanitorium under the Sign of the Hourglass:

‘And then there’s Bruno Schulz, using trains (in several different ways – history as both inside and outside the train itself, on the rails as well as in the corridors) to think about the alterity of history and alternate possibilities. I’m increasingly interested by the idea of the multi-track nature of railroads, let alone Grabinski’s sidings, as key to their importance. There’s this astonishing passage in his ‘The Age of Genius’ in The Sanitorium under the Sign of the Hourglass: